12 — 14.05.2017

El Conde de Torrefiel Barcelona

La posibilidad que desaparece frente al paisaje

performance

Spanish → FR, NL | ⧖ 1h20 | € 16 / € 13

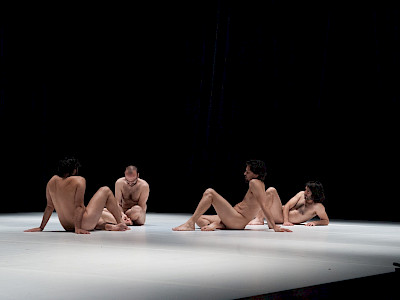

Since forming in 2010, El Conde de Torrefiel has continued to shake up the international theatre scene. Keen on blending genres and forms, comprising theatre, choreography, music, video and narration, the young Spaniards take a scathing look at today’s Europe. This is the company’s third visit in a row to the festival. In La posibilidad que desaparece frente al paisaje the company is embarking on a new stage in their work, one that is closer to abstraction. But while the images, bodies and words might appear to be disconnected, their confrontation only becomes more laden with meaning. The show takes the audience on a tour of ten European cities chosen for the fantasy world they convey. Four performers and a phlegmatic voice-off populate these ten landscapes, expressing different viewpoints about a continent steeped in history. A clean line is drawn between the map and the territory, revealing the barbarity buried beneath the agreeable beauty and extreme passivity of our everyday lives. Whether they are the statements of anonymous individuals or famous intellectuals, the words read out or heard in this powerful work invite us to question what we ourselves actually see.

Interview Tanya Beyeler & Pablo Gisbert

When and how was the company El Conde de Torrefiel founded?

Tanya Beyeler The company turned professional in 2010, when we started producing our own work in public. Until that point, El Conde de Torrefiel had allowed Pablo Gisbert to present little pieces or exercises outside the academic framework of the Royal School for Dramatic Arts [RESAD] in Madrid or the Drama Institute in Barcelona where he was studying. To start with our intention was for El Conde de Torrefiel to be a collective project, but very quickly we realised that it was an ideal that was hard to put into practice so Pablo and I took over running the company. But every show is conceived collectively. What is constant is that the scripts are always written by Pablo, but the final form comes from the combination of individuals who have taken part in the creation. It’s the choice of people we work with that determines the show that comes out of it. That’s how it’s a collective creation.

When do you write the scripts for your shows?

Pablo Gisbert When we create a show, the text always comes last. We start with a choreography, a dynamic or a composition of movements in the space. The starting point for our work is what we’re going to reveal, the colour of the show. We don’t give the actors a script. In La posibilidad que desaparece frente al paisaje, the four performers on stage are an actor, a dancer, a poet and a musician. For two or three months, we work without a script. We meet up outside rehearsals, we discuss subjects that interest us, fairly ordinary things: love, death, family, money, friends… and it’s only in the last couple of weeks that I start writing, taking into account all these exchanges and the work we’ve done during rehearsals.

TB Then in the final days, we combine the words and images and look for possible articulations. It’s also a question of confidence. While Pablo is thinking about the script he’ll end up writing, we concern ourselves with the form. We work separately, but within the same creative process. It always ends up coming together. The puzzle always ends up being solved.

PG It’s dance more than theatre that interests us, abstraction on stage. We’re not looking to develop an intellectual construction; we prefer other forms of life that can be illogical or contradictory. It can seem paradoxical given that for an hour and a half we’re presenting a text to be read. But starting a creation is like heading off on an adventure. A primarily physical adventure.

Where do you fit in the contemporary Spanish scene?

TB Our early shows used to be programmed for three or four days in alternative theatres. All that changed with our third play, Escenas para una conversación después del visionado de una película de Michael Haneke [Scenes for a conversation after viewing a Michael Haneke film], which started touring outside Spain two years after its premiere. Spanish companies are becoming much better known abroad, but there are alternative spaces in Spain without which El Conde de Torrefiel would not be what it is today. For example I’m thinking of the Teatro Pradillo in Madrid or Antic Teatre in Barcelona. Teatro Pradillo programmed Escenas para una conversación después del visionado de una película de Michael Haneke for two weeks – an almost suicidal decision! – at a time when no one knew us, but their strategy paid off: every day there were more and more people in the audience. That was in 2012 and since then Teatro Pradillo has opened its doors to us every year. For example we were welcomed there as part of the project El lugar sin límites [The place without limits], which enabled us to rub shoulders with other Spanish artists like Rodrigo García or La Ribot, as well as Argentina’s Federico León. In 2013, that was where we presented La chica de la agencia de viajes nos dijo que había piscina en el apartamento [The girl in the travel agency told us there was a swimming pool in the apartment] during the Festival de Otoño a Primavera, which takes place in Madrid every year and allowed us to be seen by a wider audience, even if it wasn’t straightforward presenting our work in an institutional setting and before an audience we’re not familiar with.

Are there links between your work and that of other Spanish artists?

PG I’m 33. When I was 20, I went to see shows by people who were 33 at the time. I’m very interested in the work of companies like El Canto de la Cabra and Lengua Blanca, artists like Angélica Liddell, Rodrigo García, Roger Bernat and Tomás Aragay, and choreographers like Elena Córdoba and Sofía Asencio. And I have lots of affinity in particular with artists on the tea-tron.com website: it’s a virtual community that doesn’t exist in flesh and blood but I feel very close to them.

TB I don’t feel that I belong to an aesthetic family. If there is a family, it’s because we share the same present, but there’s a great variety of forms between us.

What is the guiding principle behind La posibilidad que desaparece frente al paisaje?

TB Our aim was to create a contemplative space on stage, a space of reflection more than action. It was about creating a pause. We needed it. That’s what the title is referring to: it’s about landscape, so about contemplation and reflection as well. From there, other questions are asked. What are we looking at? What is hidden beneath the landscape we see? What comes out of it is the idea of a hidden war.

PG The show is also underpinned by the notion of diversion. Scenes of acting, shows, social get-togethers, cultural events, conferences, concerts and photographic sessions are represented in it… Our lives are filled with activities – theatre, cinema, concerts, get-togethers, meetings, conversations on WhatsApp, shopping in the supermarket etc. – but we’re experiencing the most absolute passivity. This schizophrenic contrast between extreme activity and extreme passivity is one of the drivers of the play.

TB One of our references is Michel Houellebecq’s book The Map and the Territory: there’s the outline of the territory on the one hand and thenwhat is hidden behind it, the real material. What’s beneath this geology,what transpires beneath this ground, what is its history, its past? Theshow is made up of images tinged with beauty and tranquillity, butthe words projected or uttered in the voice-over are much more violent,aggressive even.

The show contains references to Michel Houellebecq, Paul B. Preciado, Spencer Tunick and Zygmunt Bauman among others.

PG All the words in the show are made up. We attribute the words to these people, but it’s fiction. We use their image so that we can manipulate it. There’s nothing of a documentary in it.

TB They’re cultural idols, icons, pagan gods. But our idea was also to talk about situations involving intellectuals and unknown people who offer different points of view on the world while sharing the same time and space. It’s about collective, simultaneous experiences, but experienced in very different ways on an individual level. Hence the ten landscapes, which correspond to ten cities: Madrid, Berlin, Marseille, Lisbon, Kiev, Brussels, Thessalonica, Warsaw, Lanzarote and Florence. On the same planet and at the same moment, people are having completely different experiences. We can look at the same landscape together, but we don’t share the same experience.

How did you choose these ten cities?

PG We chose Madrid first because that’s where the piece was created. And then even though Spain is a country populated by fascists, it’s still a beautiful country. So we start with Madrid.

TB You also have to bear in mind the fact that each new landscape is announced by the name of the city, projected on a six-metre wide screen. The word is an image in itself. We’ve chosen the images according to the name of the city: its sounds, what it evokes, the imaginary world conveyed by the word, the aesthetics of the name.

PG Not all of them are capitals, of course, but they are European cities, more cities of southern and eastern Europe. Imagine a tour of Europe for Japanese tourists: “See Europe in ten days” or “Lisbon in ten minutes”…

TB But it’s the landscapes that are hiding plenty of things. I’m thinking of Claude Lanzmann’s film Shoah, which shows forests and bucolic landscapes, but then goes on to reveal the massacres that happened in that very place, years before. The words tell of the horror while the viewer sees meadows and forests. At the end of The Map and the Territory, Jed Martin, who spent his life photographing objects, Michelin maps, decides to film objects abandoned in nature, that are being devoured by nature. In the end, there won’t be anything left of us either.

PG The concentration camps have made way for beautiful landscapes and if no one remembers the horrors that took place, you might think that nothing ever happened there. What we want to show is the barbarity, the nasty things buried beneath these ten cities, as if there were two possibilities of landscape on either side of a horizontal line.

Interviewed by Christilla Vasserot for the Festival d’Automne in Paris in 2016

Translation: Claire Tarring

Conceived & devised by

El Conde de Torrefiel, in collaboration with the performers

Direction & dramaturgy

Tanya Beyeler & Pablo Gisbert

Text

Pablo Gisbert

Performed by

Tirso Orive Liarte, Nicolás Carbajal Cerchi, David Mallols & Albert Pérez Hidalgo

Voice-off

Tanya Beyeler

Light design

Octavio Más

Scenography

Jorge Salcedo

Music

Rebecca Praga & Salacot

Sound design

Adolfo García

Choreography

Amaranta Velarde

Technical direction

Isaac Torres

Dramaturgical advice

Roberto Fratini

Text translation

Marion Cousin (French), Ann Helena Remans (Flamish)

Presentation

Kunstenfestivaldesarts, Zinnema

Production

El Conde de Torrefiel (Barcelona)

Co-production

Festival TNT – Terrassa (Barcelona), Graner, centre de creació (Barcelona) & El lugar sin límites – Teatro Pradillo – CDN (Madrid)

With the support of

Iberescena, La Fundición Bilbao, Antic Teatre (Barcelona), ICEC – Generalitat de Catalunya, Institut Ramón Llul, INAEM – Ministerio de Cultura