30.05, 31.05, 02.06, 03.06.2023

Over the past ten years, through graphic art and murals, the work of Victoria Lomasko has been a ceaseless counterargument to the official Russian narrative. Her pen portrayed situations and protests in various Russian cities, creating an invaluable political counter-archive. Previous works include Feminist Travels, a graphic art coverage of the Pussy Riot trial; and the book Other Russias, which bears witness to the dissident vitality of the Russian pro-democracy and LGBTQIA+ movements. Under pressure in Russia for several years, Lomasko fled Moscow shortly after the invasion of Ukraine, knowing she had become even more of a target. She took refuge first in Brussels, then in Germany. Despite her position as a political opponent, she at times faces exclusion in the West because of her Russian passport. For this edition of the festival, she created Five Steps, a lecture performance composed of words and live drawing. By talking and sketching, she recalls the life of a dissident artist in five steps: Isolation, Escape, Exile, Shame, and Humanity. In this unique form, Victoria Lomasko gives shape to the daily life under Putin's regime while questioning the production of narratives during a war, and the possible role of an artist.

Five steps: excerpts

1. Isolation

All my visas lapsed after the pandemic began in 2020, and it was impossible for me to acquire any new ones because I didn’t have access to foreign vaccines. So I spent two years in Russia without ever leaving. I roamed around my neighborhood in search of subjects for new work. […]

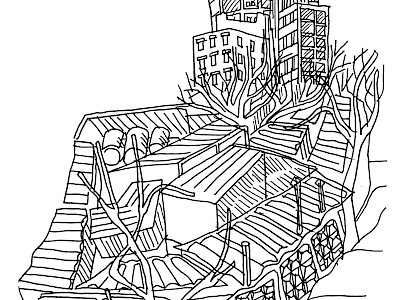

[…] On the subway I occasionally ended up on the so-called Victory Train, which was decorated with photos of Soviet soldiers holding automatic rifles and anti-fascist posters. At first I tried to avoid the warning signs, but then I decided to describe and depict them. A number of times I went out of my way to visit the Patriot Park museum complex, where tanks are lined up in endless rows and the huge expanse is dotted with militaristic statues. At the park’s entrance is the Main Cathedral of the Russian Armed Forces, which resembles a horror movie castle. It was there that I understood that the Putin regime would pull us inevitably into a new war. It was there that I found the subjects for my new work: the gloomy forest, whose branches transform into automatic weapons and Soviet monuments that come alive to take revenge.

2. Escape

I understood that if I stayed in Russia the police would soon break into my apartment. They would rifle through my drawings, read my writing, and destroy my archive. There is no justice in Russia: I could be imprisoned for three years, or maybe a decade. Putin could announce martial law at any time. He could close the borders. I began to have panic attacks. I had to change my shirt and my socks three times per day. My body was covered in a cold sweat. It would have been easier for me to run in the middle of a crowd, to throw stones and try to burn down everything in my way than to feel … how did I feel, exactly? The whole time I kept thinking of the footage from Kabul International Airport in 2021: the last airplane takes off and a crowd of people hoping to escape into the free and open world is left behind on the runway.

3. Exile

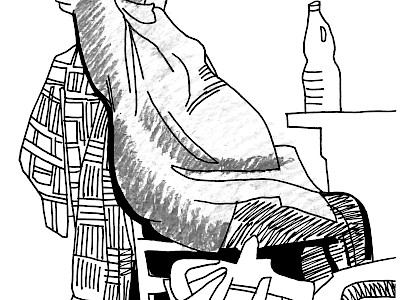

Why didn’t I bring my favorite calligraphy pens with me? Why didn’t I bring my favorite drawing pens? That tiny pen box wouldn’t have taken much room in my suitcase. I’m standing in the middle of Schleiper, a huge art supply store in Brussels. It’s my second day in Belgium and I’ve come to buy drawing materials.

When tragedy strikes, rational thought is abandoned. I don’t think about the elderly parents I’ve left behind; about the friends in danger in Russia; about my Moscow apartment, which I’d transformed over the years into a cozy workshop. I think about my pen box.

4. Shame

What did we feel? Anguish. Grief. Shame that the criminal Putin regime was committing all these new crimes in the name of Russian citizens. Did we feel collective guilt? I didn’t. For over a decade I’d done as much as a political artist could. [My friend] A. didn’t feel guilty, either. She was born in the provinces and had worked hard to get to Moscow. She financed her own social and political filmmaking, worked with migrants from Central Asia, and participated in every possible protest action. Even so, as we sat at someone else’s table eating our pasta, it seemed to us that we were in the presence of shadows – the shadows of people fleeing the bombing in Ukraine.

5. Humanity

When we’re involved in larger historical processes, every person’s choices fall somewhere on a spectrum that includes crime, indifference, and heroism. It is obvious that a person who calls for murder and destruction in Ukraine and a person who helps refugees in Russia at great personal risk represent two absolutely different universes. Behind these choices is someone’s entire life: the millions of little choices made up to that moment. Geopolitical games that operate on the basis of clear distinctions between good nationalities and bad ones cannot lead anywhere healthy. But the idea of a single humanity composed of unique individuals is a pledge toward collective progress.

- The excerpts from Five Steps was translated from Russian by Mark Krotov, and originally published by the magazine n+1.

Presentation: Kunstenfestivaldesarts, Les Brigittines

A project by: Victoria Lomasko with the participation of A. M.

Commissioned and produced by Kunstenfestivaldesarts