19 — 22.05, 24.05, 25.05.2022

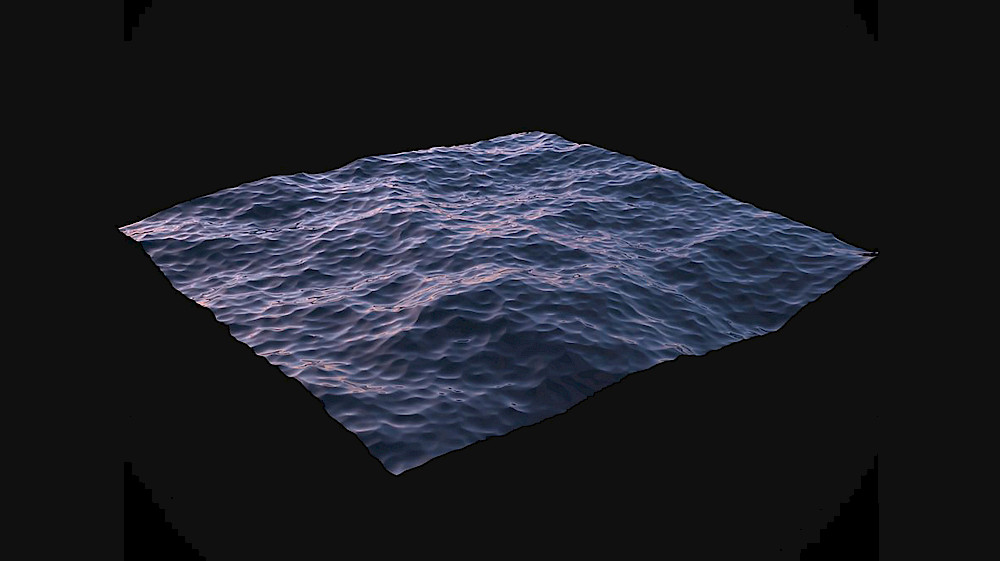

After their successful show Pleasant Island, which premiered at Kunstenfestivaldesarts 2019, Silke Huysmans and Hannes Dereere will present the final part of their trilogy on mining and our relation with resources and nature at the upcoming festival. This time, they will focus on a completely new industry: deep sea mining. In the spring of 2021, three ships converge on a remote part of the Pacific Ocean. One of them belongs to the Belgian dredging company DEME – GSR. Four kilometres below sea level, their mining robot scrapes the seabed in search of rare metals. On another ship, an international team of marine biologists closely monitors the operation. A third ship completes the fleet: on board the infamous Rainbow Warrior, Greenpeace activists protest against this possible future industry. From their small flat in Brussels, Silke and Hannes connect via satellite to the three ships, each representing a pillar of the public debate: industry, science and activism. From a series of interviews and conversations, an intimate portrait emerges via a poetic quest. It is an attempt to capture a potentially pivotal moment in the history of the earth. How much deeper can we go and what are we as humans digging towards?

Out of the Blue

Mélanie Jouen interviews Silke Huysmans & Hannes Dereere

Mélanie Jouen: After Mining Stories, about the 2015 mining disaster in Brazil, and Pleasant Island, about the extractivism that destroyed the Pacific island of Nauru in the 20th century, you’re finishing off your mining trilogy with an exploration of potential mining of the sea bed in Out of the Blue. What are you bringing up out of the abyssal zone?

Silke Huysmans & Hannes Dereere: Pleasant Island concluded with the start of underwater mineral extraction and it was an obvious area for us to explore. We wanted to learn more about it, make people aware of it and encourage them to find out more themselves because the notion of the “green transition” in the media is overshadowing the complexity of this “new gold rush”. People say that by mining these resources at the bottom of the sea, we’re avoiding deforestation or the production of toxic waste and helping to reduce the mining industry’s environmental impact. Our title also evokes the sense of feeling blue, being melancholic: out of the blue is also an attempt to stop feeling sad.

In May 2021, you followed three boats by satellite that were gathering at the Clarion-Clipperton fracture zone in the Pacific, west of Mexico. One belongs to the mining industry, another to scientists and the third, the Rainbow Warrior, to Greenpeace. Like your earlier projects, you’re conducting an investigation. How did you make contact with these protagonists?

The UN has declared the seabed to be the common heritage of mankind and this geological zone, which is in international waters, is administered by the International Seabed Authority. Marine extraction has still not been authorised, but a few countries have obtained an exploration licence, including Belgium and France. It turns out that in spring 2021, a Belgian mining company tested a prototype robot that allowed the extraction of the first polymetallic nodules 4500 metres down. Alongside them, an independent group of scientists were there to study the impact this extraction might have on the local ecosystem. We contacted them by satellite so that they could explain their approach to us. The coordinator of the mission is aware that other voices are communicating their research beyond the scientific media. Greenpeace was very easy to approach. And we had a long written conversation with the team from the mining company while they were there and met their CEO when they were back in Belgium.

Can you tell us about your particular creative process, which is both journalistic and artistic?

We initially focus on scientific research that we then document, and it’s only at the end of this phase that we transpose our approach artistically to the stage. Our material consists of lots of recorded conversations with sound and image, our investigations, the connections that sometimes fail, due to the instability of the network. In our trilogy, each piece comes about from the same process, but their forms differ since they are adapted to the research content and experiences. In this case, as it’s impossible for a human being to go 4000 metres under the sea, exploration of the ocean depths is done remotely with the help of cables at the end of which, after a four-hour descent, a robot films and takes a sample from the surface of the seabed to extract nodules. So on the boat of the mining company or of the scientists you have to imagine a black room lit up by several monitors, like windows on a quasi-inaccessible world that mankind is discovering for the first time. It’s fascinating. This remote work, our interview by satellite from our apartment – thanks to the proximity the internet gives us – this dependence on technology and its components also make up our story. This distance also allows us to have a better understanding of the challenges of mining with regard to energy, the economy, the environment and science.

How do you transpose these different arguments or narratives to the stage that are provided by the scientific, industrial and activist communities?

On stage, we recreate this room, which is both a control room and the flat where we did our interviews. The darkness of this room brings us closer to the ocean depths where everything is slow and dark, the home of organisms that are so different from the ones we’re familiar with that we can’t even imagine them. We’re trying to shine a light on this natural ecosystem and this other specific human ecosystem, and understand the challenges faced in this marine quest. Like a jigsaw, we piece together the way in which the facts and their stories interact. The scientists benefit from the mining for their research and are warning us of the threats to biodiversity. The mining company justifies deep-sea mining by the need to maintain economic growth and respond to the rise in demand for metals, while countering resource depletion and “terrestrial” pollution. The activists are exposing the risks of this potential mining and are alerting the public to it.

Only around 10 % of the world’s seabed has been mapped and explored. Your work underlines the paradox of mining exploration like this since a biodiversity we’re unaware of is being discovered and yet is being threatened by mining.

That’s right. The scientists are independent and are being funded by the European Union, but they wouldn’t be able to do this kind of research without industry. The history of geology has always been linked with mining: it’s because one day you’ll be making a hole knowing what this soil contains. A part of the play questions the role of science in society and in climate change. The geographical distance seems to remove this subject from our context and yet these impacts will indirectly affect us. We’re interested in this relationship of perception between geographically close and distant phenomena as much the temporal scale: the rare mineral ores lodged there have taken millions of years to form and mankind could break them up in a few years.

The first two creations in the trilogy were retrospectives while Out of the blue is about the future. How has that changed your research and your writing?

This opportunity to look to the future had an impact on our research because we’re close to the here and now, what’s happening is making us reflect on our actions as we’re doing them and their impact on the kind of future we want. There’s an interesting phenomenon that we all face one day: the more knowledge we acquire about a subject, the more uncertainty there is. At what point can we get bogged down in wanting to understand and embrace a complexity that is beyond us? And once we start to see things and grasp things, we also become aware of our role, of our attempt to control them.

As artists, is there a requirement or a duty for you to make the public, the theatre audience, aware of these facts and the crucial questions they pose?

As artists, the conversations we’ve had invite us to reveal all the different viewpoints on this issue. We think it’s important that the audience form their own opinion and accept responsibility. As with any editing, by combining these perspectives, our sensibilities are expressed but we’re careful to ensure the dramaturgy makes it clear what’s subjective. We want this subject to be discussed, to not be left in the hands of the researchers, mining companies and activists. We want to contribute to the public debate through poetics and encourage people to think about it.

- Mélanie Jouen, April 2022

Presentation: Kunstenfestivaldesarts, Beursschouwburg

By and with: Silke Huysmans & Hannes Dereere | Dramaturgy: Dries Douibi | Sound mix: Lieven Dousselaere | Technique: Korneel Coessens, Piet Depoortere, Koen Goossens and Babette Poncelet | Outside eye: Pol Heyvaert | Subtitles and Dutch translation: Marika Ingels | French translation: Isabelle Grynberg

Production: CAMPO | Coproduction: Kunstenfestivaldesarts, Bunker-Bunker, Ljubljana, De Brakke Grond, Noorderzon – Festival of Performing Arts and Society, Zürcher Theater Spektakel, Beursschouwburg, PACT Zollverein, Théâtre de la Ville, Festival d’Automne à Paris

Residencies: KWP Kunstenwerkplaats, Pilar, Bara142 (Toestand), De Grote Post, 30CC, GC De Markten & GC Felix Sohie

Special thanks to: John Childs, Henko De Stigter, Patricia Esquete, Iason-Zois Gazis, Jolien Goossens, Matthias Haeckel, An Lambrechts, Ted Nordhaus, Maureen Penjueli, Surabhi Ranganathan, Duygu Sevilgen, Joey Tau, Saskia Van Aalst, Kris Van Nijen, Vincent Van Quickenborne and Annemiek Vink | Thanks to: all conversation partners and the people who helped with the transcriptions