23 — 26.05.2024

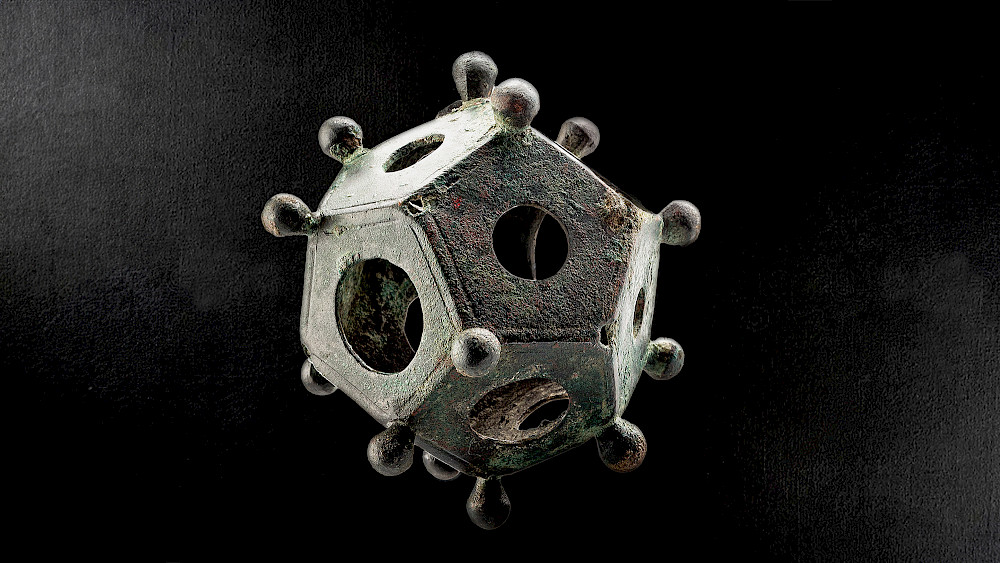

Deep inside a salt mine in the Austrian Alps lies an archive created by ceramist Martin Kunze that he calls “The Memory of Mankind”. Since 2012, he has crafted a collection of ceramic plates containing text and images to ‘back up’ human civilisation and preserve all existing knowledge about our modern times. Kunze’s ultimate aim is to create a time capsule that could last millions of years, hoping that future civilisations will find the archive and learn about our story. But what do you want people a million years from now to know about us? How do you even start? And what gives one man the right to tell the story of everyone? In this captivating theatre performance, the Swedish director Marcus Lindeen and the French dramaturge Marianne Ségol ingeniously interweave the tale of Martin Kunze with other true stories. Among them, we meet a man who suffers from a rare type of amnesia that wipes his memory clean, and a queer archaeologist who questions our relationship to history. Bringing the characters and audience together in the same space, the performance poses an existential question: why would it be better to remember than to forget?

Memory of Mankind

What inspired you to create Memory of Mankind?

Marcus Lindeen – During the first lockdown, in March 2020, I came across a project by an artist called Martin Kunze in an article in The New York Times.

Deep in a salt mine in the Austrian mountains lies a time capsule. For the last ten years or so, Martin Kunze has been inscribing the knowledge of our civilisation on ceramic slabs, in the hope that one day future humans will be able to unearth it. According to him, this is the most resistant ma- terial available and should therefore enable these archives of humanity to remain legible for several thousand years, perhaps hundreds of thousands of years.

I’m interested in all the questions raised by this extraordinary initiative: what gives Martin Kunze the right to tell our collective story? What deserves to be remembered, ‘saved’? Basically, what constitutes our history? Ever since finding out about that project, I’ve wanted to tackle these questions in a performance piece.

Your performance is about Martin Kunze’s project, but also about other stories. What’s the link between them?

Marianne Ségol – Memory. As in our previous productions, we decided to combine different stories around a common theme. Here, we will hear from an amnesiac suffering from a condition known as dissociative fugue, which causes him to lose his memory on a regular basis. Then there’s the wife of this individual, an author, who helps him reconstruct his memories through writing. And finally, there’s a queer archaeologist, who proposes to tell the story differently – from the point of view of those who are not given a voice, those who are generally forgotten in the field of historical studies.

What is the point of making these narratives resonate?

ML – When I was working as a journalist, I felt frustrated by having to stick to a particular subject and a specific format. I found it restrictive and reductive. Theatre allows for unique encounters, encounters that would not take place in real life. The stories that intertwine in our piece are true stories that are enriched through discussion and exchange.

MS – The challenge is to put these testimonies into perspective. Because they complement and problematise each other. Because the intimate is linked to more general issues. For example, in Martin Kunze’s work, the author of our piece becomes a sort of archivist for her husband who is losing his memory. And, like the Austrian artist, she assumes the right to tell his story. It raises the question of what should and shouldn’t be remembered.

Once again, you’ve opted for a minimal theatrical device: non-professional actors, close proximity to the audience, a virtually non-existent stage...

MS – Absolutely. The scenography was conceived such that the audience could enter a confined space, like a box. We wanted it to feel like a discussion space. The idea is that the audience has the impression of being included in these conversations, even if they don’t necessarily engage in discussion with those who are performing.

ML – We practise a form of theatre that is not a theatre of plays, or even of actors. The text is the driving force behind the plot. I gather the testimonies that interest me in real life; I transcribe them, and it’s only then, in the writing, that fiction can take hold. We direct and record professional actors who embody these texts. And afterwards, during the performances, we transmit these recordings into the earpieces of non-professional actors, who, in turn, make the texts their own – they don’t have much room for manoeuvre. Artistic direction takes place at the writing and recording stages.

This method is one of your trademarks. What is its advantage?

MS – In traditional theatre, actors are able to anticipate what they’re going to say and project themselves into the next few minutes. Here, the non-professional actors don’t have to learn their lines by heart – they are, in a way, spokespersons. Thus, the relationship to the present is more immediate.

ML – But for the stage, we always choose people who have a particular connection with the subject matter. This time, the queer archaeologist is an academic who works on queer issues. Martin Kunze is played by an astrophysicist working on a similar project. This theme resonates with them in some way.

MS – It’s a theatre of text, where the word becomes the main character.

Let’s get back to the theme of the performance: memory. With digital technology, we’re all leaving indelible traces on the internet, social networks, clouds... Isn’t forgetting emerging as the humanist issue of the moment?

MS – Forgetting is consubstantial with memory. Initially we wanted to include the testimony of a woman with hypermnesia –in other words, a woman with an extraordinary memory. Her problem is that she cannot tell her own story, she can’t sort it out. She’s overwhelmed. I’m not sure that digital technology will do much to change that. Machines have memory, but not memories.

Unlike writers, filmmakers and painters, the work of directors disappears along with them... Does this question of the ‘trace’ torment you as performing artists?

MS – That’s what is special about theatre: its ephemeral aspect... Which is very frustrating, and at the same time very beautiful... I like the idea of creating a perishable work about memory.

- Interview conducted by Igor Hansen Love

Presentation: Kunstenfestivaldesarts, KVS

Writing and directing: Marcus Lindeen | Concept: Marcus Lindeen & Marianne Ségol | Dramaturgy and translation: Marianne Ségol | Cast: Jean-Philippe Uzan, Axel Ravier, Sofia Aouine, Driver | Voices: Gabriel Dufay, Julien Lewkowicz, Olga Mouak, Nathan Jousni | Music and sound: Hans Appelqvist | Set design: Mathieu Lorry-Dupuy | Lighting design: Diane Guérin | Costume design: Charlotte Le Gał | Casting: Naelle Dariya | Stage direction: David Marain | Sound technician: Nicolas Brusq | Video technician: Dimitri Blin | Production, diffusion, administration: Emmanuelle Ossena, Charlotte Pesle Beal, Lison Bellanger - EPOC productions

Production: Company Wild Minds | Coproduction: Kunstenfestivaldesarts, Piccolo Teatro di Milano-Teatro d’Europa, T2G Gennevilliers, Festival d’Automne à Paris, Le Quai ‐ CDN Angers Pays de Loire, La Comédie de Caen – CDN de Normandie, Wiener Festwochen, Le META-CDN Poitiers, CDN Besançon Franche-Comté, Le Grand T Nantes, Le Lieu Unique Nantes, PEP Pays-de-Loire

Project supported by the Ministère de la Culture – Direction régionale des affaires culturelles

With the support of the Fondation d’entreprise Hermès

Performances in Brussels with the support of the French Embassy in Belgium and the Institut français Paris as part of EXTRA, a program that supports French contemporary creation in Belgium