27 — 30.05.2023

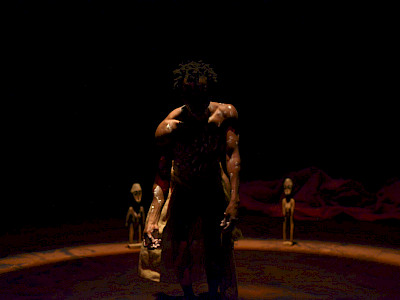

In our movement, breath, and voice we bear the elusive and mysterious traces of where we come from. In his latest creation, My Body, My Archive (2023), Congolese choreographer and dancer Faustin Linyekula digs deep into his own body which serves as a tangible archive of his country and ancestors. With Banataba (2018), Linyekula created a ritual for his ancestors in the shadow of the AfricaMuseum in Tervuren, now he continues his search for a family archive shattered by history, the fragments spread between his body and Congo. For this new performance, he takes a journey through his artistic oeuvre and family history, focusing on what was often missing in the genealogy of his family: the stories of women. He pays respect to and evokes them by a commissioned series of wooden statues crafted by Gbaga, a Lengola sculptor. Linyekula starts a conversation with the eight figures standing in Bozar’s monumental Horta Hall, accompanied on trumpet by Heru Shabaka-Ra of the Sun Ra Arkestra. In this moving dialogue, maternal ancestors recount the past in Lengola land while Linyekula dances their presence in his life today.

My body, my archive (2023)

My name is Kabako, I am Kabako. Once more, Kabako – forever Kabako. It’s me, Kabako, yes, I am a storyteller.

Spectacularly Empty… Triptyque sans titre… Radio Okapi… Le Festival des mensonges… Sur les traces de Dinozord… Pour en finir avec Bérénice… Le Cargo… Hamida et les brouillards… Congo… Drums and Digging… Statue of loss… Banataba… More more more future… The titles of performances created over the last 20 years. Because for more than 20 years I’ve been taking my stories to the world’s stages. Now I need to put a stop to this archive of personal creation, to question it. What parts of my body have I involved in each of these pieces? Above all, what traces of these pieces remain in my body and my gestures today?

In 2017, with Banataba, I discovered a forest village, a village on the banks of the Congo River, the land of my maternal ancestors. Since then I’ve returned regularly, in search of a family archive shattered by a history whose fragments have been scattered between the island of Tabakili and Kisangani, stories from which only the names of the clansmen emerge. What have we done with our mothers, our sisters; where are our women?

So I set off in search of the most renowned sculptor in the Lengola lands, Gbaga, nicknamed Prince, the prince of sculptors. Gbaga knows how to speak to wood; Gbaga knows how to extract forms from wood, to breathe into it the energy of the ancestors who have disappeared. He will sculpt for me the missing women of my mother’s clan. And since statues speak, I summon them all to the stage, I listen to their conversations about life as it used to be in Lengola land, and I dance the life of today, after the war, the crisis, the war…

- Faustin Linyekula

For nearly 30 years, Faustin Linyekula has conceived his dance as a way of going in search of the Congo, his country and that of his ancestors, a country of endless wars and daily tragedies. Congo is the name of an immense and multiple territory, in which distances are not measured in kilometres but in travel time. The invisible boundaries between the territories of which it is composed are blurred, elastic, porous, contagious; from the river to the city, from the forest to the mine, from the contemporary battlefield to the ancestral routes. Linyekula’s Congo is a hybrid space-time shaped by several hundred languages and cultures. A country that cannot be grasped, that does not fit within the limits of maps, at once wider and thicker, folded and scattered. Scattered because these heterogeneous territories that have always been linked are all the more inaccessible. Hence, for the choreographer it is, above all, a mirror shattered by colonisations, past and present, and by the disorder maintained from within and from without.

Yet he patiently brings together the morsels he finds. Broken, banished or forbidden, distanced, they became lost; they sometimes possess only an uncertain breath of often tiny resonances. If he is Congolese, if it makes sense to say it or to believe it, it’s in and through his body – as if his body, his voice, his breath, were living archives, engrammed, inscribed, instructed, in him, and they knew something that he himself did not.

Faustin Linyekula named his dance company Studios Kabako, after the character in Mhoi-Ceul (by Ivorian playwright Bernard Dadié), who has become the dancer’s double over the course of his creations. But this Kabako is a storyteller who would rather dance than speak. Kabako-Linyekula travels the world, invited to present his danced ‘quests’ on five continents. He carries with him this dismantled Congo as baggage and as pain, as an offering and as a burden. When envisaging a project for the 20th anniversary of Studios Kabako, Linyekula entitled it as a synthesis of his choreographic work: My body, my archive (2023). This would be an opportunity for him to retrace the path, to compose a memorial puzzle through performances that are also stages in a search for the imaginary yet present country. As well, My body, my archive can be seen as a set of quotations from past performances. Although here too, accuracy doesn’t count, the reference needn’t be certain; the attention, intuition and energy they nourish are otherwise decisive.

But this first impetus crossed a second one. For another creation, Linyekula found his way back to his mother’s clan. Since then he returned to the village from time to time, and in the end was surprised that the stories he collected there only related to male ancestors (even though the clan was named after a woman). “Where are the women?” he asked – not only to the clan members, not only to the storytellers, not only to the ancestors whom the choreographer had asked the drummers to address even if they didn’t know how to tackle that question, not only to the sculptor he presently commissioned to sculpt effigies of his female ancestors. No, he also asked himself that question, for the fragments of memory amassed during 20 years of Kabako-creations were also attached to male figures, he discovered.

My body, my archive (2023) is thus the double intertwined path of a memory to oneself, a double spiral scale connecting the buried territories of the past with the present, as if to disengage, extend, multiply the possible paths to follow tomorrow.

But then again, this is only one version of the facts, as we understand that the authenticity, the true and the certain, are not the material of these emotions. Kabako’s impulsion also causes him to follow other shores. In Kisangani, the metropolis in the east of the DRC where the dance company is based, Studios Kabako has also become a place for training and initiatives, accompanying young artists and encouraging personal and artistic approaches that are directly related to specific contexts. And for some years now, Linyekula has also exited the huge city in order to set up a new project in the heart of a vast parcel of forest, where he organises dialogues between the arts, persistent snippets of traditional knowledge and current scientific hypotheses, and local and international socio-ecological questionings. My body, my archive (2023) also bears these traces: that of a perpetual journey through separate, violent or distant territories, a journey comprising the linking of times, beings and histories, men and women, water, dwellings, forests, rivers, soil, wood, light, the burdens they carry, the forces they transmit.

In My body, my archive (2023), drums resonate; they strike a rhythm that’s reformulated, recomposed, tampered-with, to welcome Faustin Linyekula’s female ancestors when Gbaga brings in the sculptures. Further along, Uncle Ignace welcomes the same statues into his house in Kisangani, and this staunch Catholic surprises his world by talking to them as if they were relatives, welcoming them into the family home. To link is not to replay or to maintain, but to offer the possibility of inventing the dance of the present.

- Text by Éric Vautrin

- April 2023

- Since September 2015, Éric Vautrin has been the dramaturge at Théâtre Vidy-Lausanne. His works attempt to connect the history of forms and techniques, the performer / spectator relationship, creative practices, and symbolic and institutional frameworks.

Presentation: Kunstenfestivaldesarts, Bozar

Choreography and dance: Faustin Linyekula | Trumpet: Heru Shabaka-Ra | Sculptures: Gbaga | Sound design and video: Franck Moka | Costumes design: Aldina Jesus | Dramaturgy in dialogue with Eric Vautrin | Dramaturgy assistant: Dorcas Mulamba | Lighting design in collaboration with: Christophe Glanzmann | Additional music: Jamos (percussions), Passero (percussions), Mobeti (percussions), Joachim Montessuis (Nierica)

Production: Studios Kabako / Isaac Yenga | Coproduction: Chaillot – Théâtre National de la danse, Théâtre Vidy-Lausanne

With support from: Arts and Humanities Division, New York University Abu Dhabi

Special thanks to Catherine Wood and the Tate Modern, Londres