04 — 08.09.2020

Jisun Kim Seoul

The House of Sorrow

performance — premiere

Maison des Arts de Schaerbeek / Huis der Kunsten van Schaarbeek / Online

English → NL, FR | ⧖ 1h20 | € 16 / € 13 / € 0 |

04/09 | 17:00 | Au théâtre — FR

04/09 | 22:00 | In het theater — NL/EN

04/09 | 22:00 | Online on Minecraft — EN/NL

05/09 | 16:00 | Au théâtre — FR

05/09 | 16:00 | En ligne sur Minecraft — FR

05/09 | 22:00 | In het theater — NL/EN

06/09 | 18:00 | In the theatre — EN

06/09 | 18:00 | Online on Minecraft — EN

07/09 | 18:00 | Au théâtre — FR

08/09 | 18:00 | Au théâtre — FR

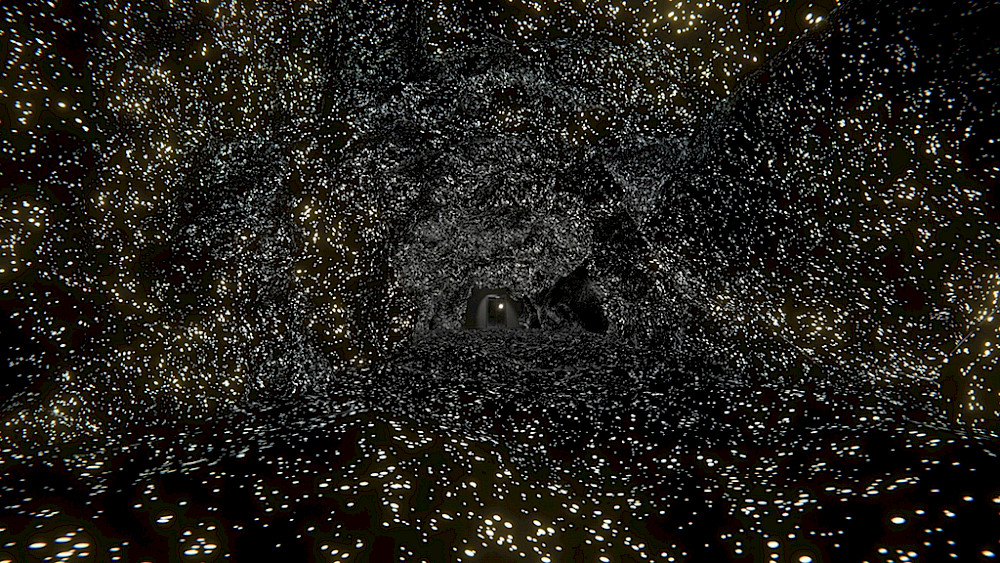

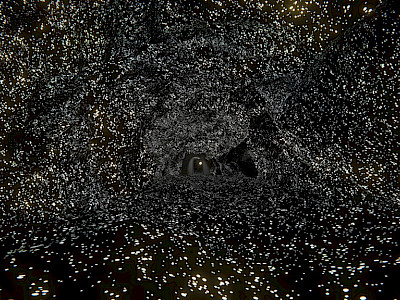

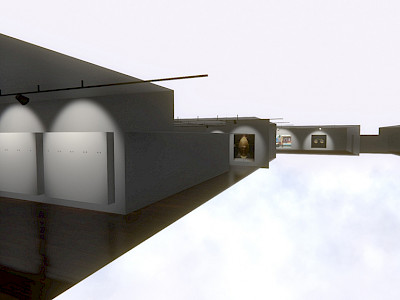

Can the virtual space become a space of freedom, through which to explore both another world and the self, while being confined in a room? The myth of “El Dorado” – according to which gold objects were immersed in a river in the course of a ritual – could also be read as the restoration of matter to its source. Extracted from nature, gold was melted to create sculptures before being returned to nature. However, if what is to be restored is a thought, then how can that thought be restored to its source? During a trip to Colombia, artist Jisun Kim happened to meet a man named Min, who handed her a USB stick containing various games. The video games were developed by Min himself. Each of these games could be read like a book, in which one can get lost in Min’s thoughts and memories. But why did Min want to tell his stories in video games that can be experienced and reinterpreted over and over again? Jisun Kim invites a professional gamer to fully unravel, together with the artist, Min’s stories and thoughts. Together they inhabit the virtual sculpture The House of Sorrow and invite the audience to dive into Min’s world with them. Two spaces simultaneously host the performance of The House of Sorrow: the physical space of Les Halles de Schaerbeek, for those in Brussels, and a theatrical space built by the artist inside Minecraft, and accessible for free to all its users.

Performances on Minecraft

Online performances are free. Visitors wishing to see The House of Sorrow online must have an official version of Minecraft installed on their computer. An e-mail with all the practical informations to access the performance will be sent 48 hour before the beginning of the show to the visitors who have booked a ticket.

Building games

In your work there are robots on stage, texts written by algorithms and stories developed in games. These technologies surround us in everyday life, but what made you decide to use them in the theatre?

The central question I’ve been working on in the last few years is that about how we perceive the world, how we sense our surroundings. So actually the technology itself is not the topic of my work, but rather the way we perceive our environments. Sometimes I seek to answer that question through technology, sometimes I don’t. For Deep Present (shown at the Kunstenfestivaldesarts in 2018, Ed.), a performance with four types of artificial Intelligence on stage, it began with research on outsourcing issues. I didn’t initially think about artificial intelligence, but my research led me to the idea that automation could ultimately lead to the outsourcing of our ability to reason. So then I thought about this format of the performance where there are forms of AI on stage that have studied humans and technology through human data, and talk about human systems such as outsourcing, but also about anthropocentrism and wars. The technology follows on from the concept itself.

In The House of Sorrow you work with video games. What brought you to that medium?

First I thought about ways of storytelling, about various forms for telling a story. When you play a game, the possibilities of storytelling are quite different from any other medium. The most distinctive feature of games is, I think, that it has a first-person perspective experience. So when you are ‘in’ the game, you can experience the story from within that space. I wanted to unfold my concept in this space, in this gaming way of storytelling.

Could you tell us a bit more about how storytelling in a game actually works and how you use it in your performance?

One option could have been to screen the game and give the audience the feeling that they are playing the game themselves. But I work with a mediator, a game performer who is a professional gamer, so it’s actually more about the game-streaming culture, not the game itself. For a while I was surprised to learn how people nowadays are more interested in watching others playing a game than in playing the game itself. I decided to dig deeper into this game-streaming culture to help tell my story.

The role of the gamer is very important in The House of Sorrow because the audience has access to the game experience only through the gamer’s translation. There’s also my voiceover narration inside the game, but the person who translates from the screen to the spectator is the actual performer. So there are lots of layers of storytelling in this performance: that of the game, that of the gamer and that of the voiceover.

The gamer can vary depending on where the performance is being shown. The character of the gamer, their personality, energy and way of playing, greatly determines the colour and content of the performance. For the performances in Brussels there will be three different gamers, so that will result in three different shows even though it’s the same work. It’s like travel – it becomes a different journey depending on which guide you have.

Was there a particular kind of game you looked into?

These days there are many games that inspire me in how they can also convey philosophical ideas. For example when I was coming up with this performance, I was inspired by the narrative video games developed by David Wreden called The Stanley Parable and The Beginner’s Guide. I also looked into Getting over it, a game in which you are Diogenes, the philosopher in his jar, and you have to climb all sorts of mountains only using your arms and a hammer. It’s very difficult and you nearly always fall down. There’s also a philosophical narration over this game, which tends to disappear into the background because people get too frustrated. The developer of this game told me that he created it with a particular type of person in mind, to hurt them. But that seems to be precisely the focus of the game itself: this tension between trying to accomplish a task or action and listening and reasoning. These games provide inspiration for thinking about storytelling and about how audiences can experience the work.

We can watch The House of Sorrow in the theatre space, but also in a virtual space, in fact a theatre that you built in the game Minecraft. How do these experiences differ?

There’s not really a ‘better’ option. The meaning of watching it in Minecraft is that you can be with other players/spectator avatars, there’s a kind of mirror because you’re a gamer watching a gamer. You can also get around the map. While I was working on an earlier performance, Climax of the next scene (shown in 2016 at the Kunstenfestivaldesarts, Ed.), I met a lot of players of games like Minecraft, GTA and World of Warcraft. At that time, like we’re doing now, we contacted each other on Skype. So while we were talking, we met inside the game as characters. That really made an impression on me because when I met the other person’s character in the game, it felt like we were face to face. Not the same as in a traditional face-to-face, but nevertheless there’s a kind of sense of being together inside the game. For the online performance of The House of Sorrow, I wanted to create the opportunity for the audience to feel this being together in the game, because it’s difficult to imagine without actually experiencing it.

Personally, I have high expectations of online performances this time. You know, I tried to release the game from The House of Sorrow on Steam, a gaming platform, but I didn’t have the budget to optimise it so that it could meet the requirements. That would have been a whole other experience again, one I’m still curious about.

I’m still interested in this story you want to tell through the games. Was there a particular starting point for that story and for this particular work?

A few years ago I found a book in a bookstore by chance, and the book said that after the Buddha reached enlightenment, he recited a poem which said: “Builder of the house of sorrow, you will not build the house again”. I realised I had built so many houses as well, and I wanted to create a work one day starting from this phrase.

At that time I thought a lot about the formation of an idea and how you record that idea, how you materialise it and if it would then still be possible to transform this idea again. When I was doing research in South America a few years ago, I stumbled across the story of El Dorado. Some versions of the story say that the people of El Dorado threw their gold back into the lake. They didn’t do it just because they had a lot of gold. It was a ritual to return this old material, which they had shaped into a particular form, back to the nature it came from. And this action is meaningful for them. This story inspired me. For instance, can I change the shape of any intangible thought I have had and send it back to its origin, in an act of repair?

The story I tell in the performance itself has various examples of this process of transforming something immaterial in order to return it. It talks about suffering, but like with a machine, it’s only when it’s broken that you start to realise how it actually works. The same with the figure of Min in the story of The House of Sorrow: only when his body broke in an accident did he look into his own body and mind and ask himself the question of what was causing his pain.

Are ideas and other aspects of our consciousness, like memories and thoughts, our sorrows, the causes of our suffering?

Building the house itself is the sorrow. Almost everything can fall under the meaning of sorrow. I see the house as everything we gather and shape. In that sense, the house of sorrow is a bit different from what we usually understand as ‘sorrow’ in everyday life. An example I give in the performance is that of a mandala made by Tibetan monks. For days and days, several monks make the mandala by exercising extreme concentration. And then, upon completion, they destroy it. It’s a metaphor for how we can deal with our ‘houses’ and the sorrows they bring with them.

So creating this performance is also building this house? That has something very poetic about it. In my understanding of Buddha’s philosophy, life itself is suffering. We can’t avoid building this kind of house. By creating this performance, I accept that I made a lot of ‘houses’ and I try to find out how I can renovate them or how I can destroy them. That is the question of the last part of this work. Maybe it’s like in the story of Min – that in fact there is no sorrow and there is no house.

An interview by Kristof van Baarle, August 2020.

‘The House of Sorrow’ – Scriptures, Prophet, and Remediation

(…)

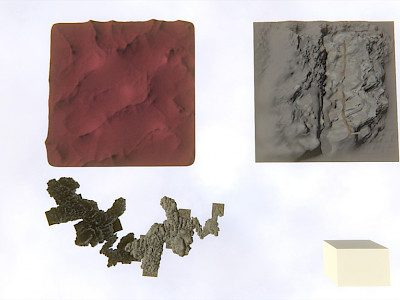

The House of Sorrow takes the format of game as medium on the surface. To put it more accurately, it’s the form of game streaming rather than game itself. The components of The House of Sorrow are roughly divide in two categories: while the inner components make up the format of an interactive adventure game playing from first–person perspective through a 3D program, the outer part, enveloping the inner components and getting in touch with the actual performance audience, doesn’t use an actual game interface, but rather a format of game streaming achieved through its player who’s broadcasting their playing.

While the game forming the inner text takes the form of a 3D first person perspective that doesn’t pursue mediation, the outer surface of streaming, along with the game playing screen as the subject of reenactment, shows the face of the actual player, and broadcasts their voice and face expression, accurately revealing the intention of the game media as the subject of replication. This novel attempt of borrowing the format of game streaming, interestingly, coincides with the aim of the repeated sentence format of ‘Thus have I heard~’ phrases, originated from the Buddhist writing format of yeosiamoon, which lies as a milestone in the narrative center of the aforementioned performance, considering they both remediate the original subject of the reenactment – ‘Min’, ‘Sakyamuni’, and ‘game’.

The performance audience stands in the same perspective as the entire sabudaejooong – the four types of Buddhism followers – who can’t listen to Sakyamuni’s preaching in person, but hears the retold versions by his students like Ananda instead. On the line of this equation, the streamer, playing the game placed in the center of the performance, stands in the same position as Ananda, meeting the outcome where Buddhist concepts and media formats are aligned under the structure of ‘the original text – the firsthand contact – the secondhand spectator’.

This, especially in contrast to the way digital game media are utilized in contemporary media art in general, creates more meaningful points. While the utilization of game in media arts has been mainly focused on interactivity, the primary characteristic of game as medium, The House of Sorrow focuses on how the interactivity is remediated as the medium of internet broadcasting, settling in as a more popular format. As a result, what’s embodied through The House of Sorrow is not game, but game streaming. And this process, in relation to the message, reveals that contemporary internet streaming doesn’t stand very far away from the preaching of early Buddhism and its transmission. While digital game has been expanding in quantity for quite some time, its actual influence as a popular culture is far weaker compared to internet game streaming. Given that, The House of Sorrow embraces both digital game and post-digital game, allowing a significant interpretation that the mechanism within the operation format of contemporary digital media’s most popular aspect can be explained through the analogy of ancient scriptures.

Especially, its performance structure intentionally excludes the interactions between the streamer and the viewers, one of the main elements of internet streaming, making its purpose stand out more distinctively. (…) However, The House of Sorrow adopts the way of leading the performance while the interactions between the audience and the streamer are blocked, which reveals this performance is closer to the media format of Ananda and such of Buddhism rather than the contemporary popular media formats. To roughly sum it up, one could phrase it as adopting the messages and formats of the Buddhist scriptures, while reconstructing the formats through contemporary media.

(…)

Therefore, The House of Sorrow rather appears to require the function of ‘multi-time play over’, one of the characteristics of digital game media as the original format. What if there was an extra play sequence where the same game contents are approached differently by another streamer? Just like how the Four Gospels of Christianity unfolded different approaches and revelations on Jesus’s achievement in a quartet-like ensemble format, the twofold remediation performance of game – streaming format could also have included a horizontal expansion, which leaves much to be desired. (…)

Nonetheless, the significance of The House of Sorrow doesn’t seem light. As game started taking up a big part as an industry, its meanings began to get exaggerated and overstated, and superficial slogans as, ‘Game is a culture,’ are taking over. Considering the situation where even media-artistic approaches to game media are staying on a superficial level, The House of Sorrow discovered and focused on streaming, another format of both remediation and limitation. In that sense, it is clear that The House of Sorrow has brought up a big question on how contemporary media art can approach game and, in a broader sense, meta ‘gaming’.

by Lee, KyungHyuk (Game Culture Researcher)

Presentation: Kunstenfestivaldesarts-Les Halles de Schaerbeek

Conception and direction: Jisun Kim

Assistant director: Yoonzee Kang

Technical director: Jimmy Kim

Game development: Doohyun Park, Gigang Moon, Ojun Kwon

Illustration: Chaewon Oh

Performers: Whitney Bovy, Guillaume Loréa, Theo Livesey

Research Assistance: Youngtaek Hong

Audio correction: Taesoon Jang

English translation: Yoonzin Kang

Dutch translation: Martine Wezenbeek

French translation: Isabelle Grynberg

Minecraft map construction: GBF Studio (Minseok Kim, Yuhyeon Jang, Jeongmin Oh)

Minecraft system: GBF Studio (Jumyung Choi)

Coproduction: Kunstenfestivaldesarts

Supported by: Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism; Seoul Metropolitan Government; Seoul Foundation for Arts and Culture

Performances in Brussels supported by: the Korean Cultural Center of Brussels