03.05, 10.05, 17.05, 24.05.2014

Christophe Meierhans Brussels

Some use for your broken clay pots

performance

English, French | ⧖ ±1h30 | 3/05, 19:00 EN (no translation) | 10/05 – 19:00 FR (no translation) | 17/05 – 19:00 FR (no translation) | 24/05 – 19:00 EN (no translation)

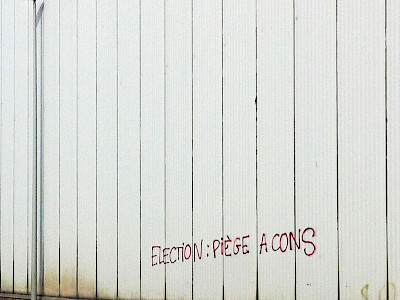

The artistic centipede Christophe Meierhans presents a remarkable piece of political science fiction. Far away from the electoral turmoil, he is working on an ambitious democratic experiment: a new constitution. More than a utopian thinking exercise, this is a serious investigation, a theoretical but inspired experiment between hope and disillusionment. In ancient Athens, citizens would carve the name of a politician into a clay pot in order to banish him and thus neutralise democracy from power or corruption. Similarly, Meierhans attempts to assimilate the principle of positive disqualification and various other ideas into a fundamentally different political system. At the festival, he seizes the opportunity to test his constitution experiment on the electoral campaigns and political notions of the year 2014. Every Saturday in May, at the festival centre, Christophe Meierhans performs his plan to the public. On the last day of the festival, the eve of the elections in Belgium, he bounces his theories back to a few political thinkers. Let your voice be heard as well!

Challenging realities – Between desire and disappointment

Bart Capelle on Some use for your broken clay pots by Christophe Meierhans

A new constitution for democratic systems – that is the remarkable starting point for Some use for your broken clay pots, a tripartite project by Christophe Meierhans. This legal text, which prescribes all the institutions, organs, laws, and procedures necessary for the establishment of a realistic and functional democratic regime, serves as the basis of a performance and the starting point for a short film. It is also available as a book. For the development of this constitution, Meierhans was advised by a team of experts. In the following interview, political scientists Anne-Emmanuelle Bourgaux (ULB), Jean-Benoît Pilet (ULB), and Dave Sinardet (VUB) share some of their experiences in working on this Promethean creation.

What is your area of expertise?

Jean-Benoît I am mainly a specialist of electoral systems – of the way they are organised and the rules that govern them in Western democracies.

Dave I mostly work on federalism and nationalism, as well as on political communication.

Anne-Emmanuelle My research is focused on democracy in Belgium. As a lawyer, I also have experience in writing legal and constitutional texts. So I was asked to hold the pen for the writing of this new constitution.

What attracted you to the idea of creating a fictional constitution?

J-B I think this project is an interesting intellectual exercise, both for us and for an audience.

D It makes you look at our current system in a different, more open way. It invites you to think critically about its advantages and disadvantages, about the potential or impossibility of alternatives. It might not completely convince people, but it can make you more open to other forms of democratic renewal.

A-E When I tell people about this constitution, within two minutes everybody is arguing. The idea of a new regime has a subversive power; it provokes staggering reactions. The current relationship of people to politics is one of desire and disappointment, which is quite sad. Studies show that there is a growing distrust of the contemporary political system – of politicians and institutions – particularly among young people. In Belgium, this disbelief is currently peaking. However, these studies also indicate a great interest in politics, although not in its traditional form. People’s capabilities in conversation and critical thinking have greatly increased, but debates, election campaigns, and newspaper articles no longer pique their interests. A project like this could bring politics closer to people again, which is where it needs to be.

Devising a constitution from scratch sounds like a titanic task. How did you work to tame this beast?

J-B I would say that Christophe is the one who solved the puzzle. In a series of meetings, we shared ideas with him on specific components of the system. Christophe then assembled them. It is still a bit of a mystery to me as to how he achieved this.

D I agree. We merely gave some input and critical reflection, based on the proposals and ideas he presented to us.

A-E My involvement was a little different. Lawyers make good soldiers: we are well trained at executing orders. So Christophe shared his ideas and I tried to express them in a legal text that would be consistent and convincing. That doesn’t mean we didn’t have discussions on the content. You can never really separate content and form. The moment of writing is really the moment of finalising ideas, and new questions still arise during that process. I think we didn’t necessarily choose what we thought ‘best’, but rather that which is at the same time most coherent to the whole, and most surprising – that which goes beyond our assumptions.

Is the experience of creating a fiction different from an academic approach?

D In academic work you generally tend to describe and analyse the current political reality. Here, you want to develop a new reality altogether. However, I think the latter is also part of an academic’s societal role: to use our knowledge as a foundation from which to imagine improvements and advocate possible solutions.

J-B Although it was quite different from my everyday work at the university, it was still quite easy to make connections. Much of our academic work is based on the comparison of western democracies with other political systems in the world. Those points of reference were also very helpful in the discussions with Christophe.

A-E There is an interesting ambiguity in the fact that a fictional system, a work of art, can provoke debate on the current system, which is real. For me, it was also a paradoxical experience to write a constitution – a legal text – that isn’t real.

Are there particular advantages or challenges when working on fiction rather than on reality?

D It permits you to leave reality aside, to think in a more creative way and to question things more fundamentally.

J-B Everything is open. You can propose ideas without taking into consideration whether they would receive enough support from political actors. And because you know that the goal is to provoke thought, you can go much further than in reality.

D I guess one of the risks would be not arriving at a stable result. Because there aren’t many boundaries or limits to this creativeness, you could continue developing new ideas infinitely.

A-E Starting from a clean slate – a tabula rasa – is unique for a constitutionalist. It is an incredible opportunity and maybe even a dangerous one. When you let lawyers create from scratch, they think they are the masters of the world. And they already think that too often anyway. But from an intellectual point of view, it’s fantastic. On the level of form, we wanted to make sure that this constitution resembles a real one as much as possible. The number of creative choices one can make seems endless. Initially I thought it could be fun to write the constitution in different colours, as legal texts are usually black on white. But in the end, we decided that we should really stress the formal, somewhat dull side of the law.

Are you satisfied with the result of your collaboration?

A-E If you were to ask me if this system could work, I don’t think I could answer that. After a while, you start loving what you are working on, whether you are an artist, a jurist, or a politician. It’s a challenge to not completely identify with what you are doing.

J-B I am satisfied because the constitution is thought provoking and innovative. That was Christophe’s main goal, I believe. It does not appear completely unreal and can be defended to a good extent. Like Dave, I think that the system proposed could have certain negative effects, but not more so than any other system.

D This new constitution also starts from the idea that the citizens have to be involved as much as possible with politics and democracy on a day-to-day basis. I think that is a very noble and worthwhile idea. In the end, it is a project about political participation and the difficulties that come with it.

If the system you put together would actually be implemented, what kind of society do you imagine it would create?

A-E I don’t believe that a constitution shapes a society; it is society that shapes a constitution. So if this constitution were real, what kind of society would it imply? That is a rock ‘n’ roll question. I don’t know to what kind of citizenship it would correspond to. I think Some use for your broken clay pots pushes the boundaries of certain traits and tendencies we observe in society today. What strikes me in Christophe’s constitution is that a political act becomes an extremely solitary one. I think it emphasises in individual citizens the solitude of their citizenship. Another striking aspect is the extensive use of new technologies to exercise one’s citizenship. The Internet will become a habitat where democratic ideas can be created, nurtured, and abolished. Utopian works of art only provoke discussion when they are revolutionary and at the same time rooted in reality. If a utopia is too radical and too removed from what you know, it doesn’t touch you. It needs a good balance of subversion and realism.

D I’ve always liked that a lot about Thomas More’s Utopia: he utterly challenges the social system of his time to encourage his readers to look beyond the norms and values of the system as they know it. Some use for your broken clay pots might not fully convince people of the political system it proposes, but it might make people more open to other forms of democratic renewal. In that sense, this project comes close to one of the roles I attribute to academics: not just researching, analysing, and describing contemporary society, but also thinking about, and possibly advocating, improvements.

Conceived & performed by

Christophe Meierhans

Dramaturgy

Bart Capelle

Conceptual adviser

Rudi Laermans

Constitutional advising team

Anne-Emmanuelle Bourgaux, Rudi Laermans, Jean-Benoît Pilet, Dave Sinardet

Constitutional jurist

Anne-Emmanuelle Bourgaux

Scenography

Sofie Durnez

Book conception & design

The Theatre of Operations

Illustration

Nuno Pinta Da Cruz

Publishing

MER. Paper Kunsthalle

Video documentation & technique

Luca Mattei

Thanks to

Adva Zakai, Anna Rispoli, Ant Hampton, Berno Odo Polzer, Bruno de Wachter, Christoph Ragg, David Helbich, Dries Douibi, Elisa Demarré, François-Xavier Lefebre, Freek Pieters, Goedele Nuyttens, Goran Petrovic, Guy Gypens, Heike Langsdorf, Helga Baert, Jessa Wildemeersch, Jorre Vandenbussche, Katja Dreyer, Kunst / Werk, Lars Kwakkenbos, Laurent De Sutter, Manuela Deschamp Otamendi, Manuel Van Rahden, Matthieu Goeury, Michael Schmid, Miriam Hempel, Miriam Rohde, Nigel Barett, Peter Fol, Philippe Chatelain, Vincent P. Alexis, a.o.

Presentation

Kunstenfestivaldesarts

Production

Mokum (Brussels)

Co-production

Kunstenfestivaldesarts, Kaaitheater (Brussels), Kunstencentrum Vooruit (Ghent), workspacebrussels, BIT Teatergarasjen (Bergen), Teatro Maria Matos (Lisbon)

Supported by

Vlaamse Gemeenschapscommissie, Vlaamse Overheid