03 — 05.05, 09 — 12.05, 16 — 19.05, 23 — 25.05.2013

Brussels

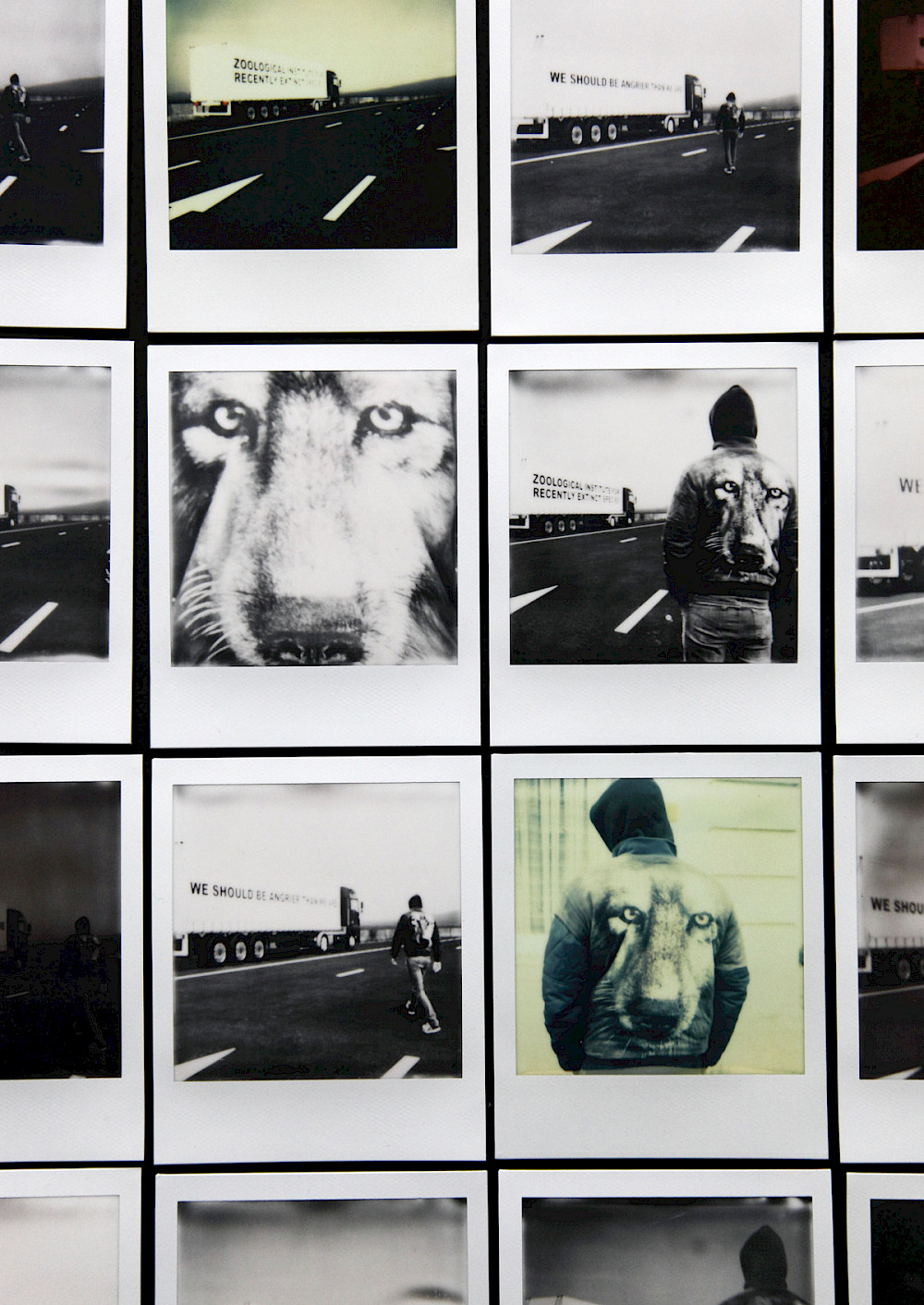

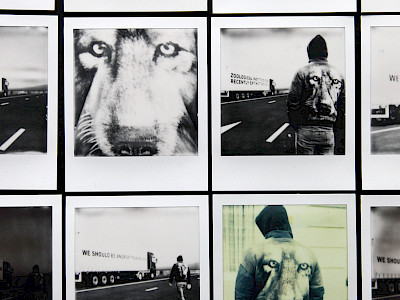

Zoological Institute for Recently Extinct Species

installation / performance — premiere

Muséum des Sciences naturelles / Museum voor Natuurwetenschappen

French, Dutch, English | Expo: Weekdays 9:30-17:00 + Weekends 10:00-18:00 + Closed on Mondays | Performance: 3 + 4 + 9 + 10 + 11 + 16 + 17 + 18 + 23 + 24 + 25/05, 21:00 — 5 + 12 + 19/05, 19:00

In 2011, Jozef Wouters set up the Zoological Institute for Recently Extinct Species with a group of scientists, activists and sympathisers. Their manifesto begins: “We should be angrier than we are”. Since then, the artist has relentlessly been poring over accounts of extinct animal species and critical moments in our natural history. In 2013, the institute has taken responsibility for constructing the monumental – and as yet unbuilt – north wing of the Museum of Natural Sciences. Using a collection of extraordinary images, observations and commentaries, the stage designer offers his viewpoint of the choices made by man in his relationship with his habitat. The temporary extension can be accessed by museum visitors during the day. After the museum closes, spectators are able to discover the story hidden behind the collection. A daring project that explains the ecological issue in an entirely novel way!

On the following pages, you can read a letter from the curator addressed to the visitors of the Zoological Institute for Recently Extinct Species, as a guide to the wing and the collection.

Dear Visitor,

I am writing this letter with the idea that you are seated in one of the 70 study places on the first floor of this wing and are looking down. Onto the collection. I picture that you have come alone. And that you have time. I picture that it is not raining but it is also not particularly sunny. Normally, before you came into our wing, you have visited the rest of the natural sciences museum. You saw the iguanodons, the mammals, the prehistoric people, and maybe even the insects. You probably skipped the minerals. In regard to our story, that's doesn't much matter.

In this wing you will get an overview of our natural history, also called ecology. The 36 images that you see down there are the 36 most important moments in our natural history. You will find a chronological list of those moments at the back of this booklet. It is important for you to know that what you'll see below is 'true'. As far as we know. We have been assembling our collection for five years. And all our information has been thoroughly checked. A team of researchers has worked on it for months. For each image, the facts were gathered and all the information repeatedly checked. Whatever still remained unclear, we have painted BLACK in our images and reconstructions.

The list is in chronological order, but it is important to know that the information was established cumulatively. In groups. At first there was only one image, one story. The story of Benjamin, the last Thylacinus cynocephalus or Tasmanian wolf. Shortly, you will be shown a movie downstairs. You'll see Benjamin, the last living Thylacinus, filmed in the Hobart Zoo in Tasmania. We have reconstructed his cage as accurately as possible, based on that movie. Downstairs, next to the mountain, is the cage. Those parts of the cage that are not visible in the film we've painted black, because we wish to strive for absolute scientific accuracy and show nothing that is not true.

During the night of 7/8 September 1936, the zookeeper forgot to open the hatch that you see in the cage below, the hatch to Benjamin's overnight shelter. Sometime around midnight, Benjamin died from the cold. When I first heard this story, I thought that this image - the story of Benjamin - should fill an entire wing of a museum. A Thylacinus wing. I imagined a wing in which the whole story of his extinction over a period of 40,000 years would be told. Without synopsis or simplification. Without having to be concise. I thought that the story of the complex, problematic domination and responsibility that man has on this planet could be summarized in one image.

But we discovered yet more stories of the extinction of last specimens of species, which also had their own name and an exact date of death. Therefore, besides Benjamin, you will also soon see Martha, Incas, Celia, Qiqi, and Orange Band. They had to be included. But afterwards we found even more stories about extinct animals, also those without a last representative. Moreover, our natural history could not be told without mentioning people, and the choices they have made. Choices that resulted in extinction. Eventually we decided that our wing would be called the Zoological Institute for Recently Extinct Species and that our collection would only consist of stories and images of recent extinctions: all animals that became extinct after 1492 would be featured. But there were important moments that needed to be added, moments not directly linked to extinctions. I had long opposed that but kept it to myself.

After a time, however, it became clear that the collection was not complete. We still needed more images. Images about harmony and images about doubt. Images that our natural history related as a series of choices, images that could not be linked to one specific species or to one human individual. Images that fit nowhere but were necessary to tell our story. Afterwards, to create order and regain an overview, we arranged all the images chronologically. The list can be found at the back of this booklet. That is the complete collection: our natural history, captured in 36 images.

Now look at the white bust down in the courtyard. That is Linnaeus. On the first of January 1756, this man officially began to arrange all life on this planet into a big list. That list is what we call 'taxonomy', the scientific classification of all living beings. He thought that it would be possible to describe the whole of nature on the basis of mutual similarities and differences. From that point arose natural history museums like this one. These museums occasionally built wings to enable them to display an overview of their growing collection. They took for granted that their collection would one day be complete. The new and the unknown were no longer a problem and were easily included in the collection. In order to retain an overview, they decided to present one specimen of each species and to preserve it for eternity. That specimen then serves as a typical example of its kind. You could put all those specimen types together on a table and organize them into groups, families, genera and subgenera. That table then presents an image of nature as a harmonious whole, onto which man can look down from above, without doubt and with the certainty that everything is comprehensible.

Our natural history is often called ecology. I've heard it said that it is the eleventh hour, that we are at the foot of a mountain and on the edge of a precipice. That it is almost too late. That we are the generation that has to make choices. That we are responsible. But of course we say that because we are a species that is not in a state to understand geological time scales. The duration of a human life is an inadequate unit of time for our impact on this earth to be measured. We have little idea of how briefly we exist. When we talk about ecology, we must start at 80,000 years ago. The ecological story begins with a dominant species that departs from Africa and populates the world, mixing ecosystems, finding oil, and entering the 21st century with a world population of seven billion people, with a lot of responsibility, too few raw materials, and above all, a total lack of adequate images. We cannot grasp the way we deal with this planet.

Our natural history is a series of choices. Of people who make decisions without knowing the consequences. A natural history museum has the task of providing us with images. The question is, which images will be able to evoke the story of a species that continually makes choices without knowing the consequences. How do you picture the not-knowing?

I picture that you are now getting up, ready to walk downstairs amongst the collection. You can stay as long as you want. You can touch the pieces as long as you do not damage them. I'm not here tonight, but if you have any questions, you can always ask the attendant.

Thank you for your visit,

Jozef Wouters,

Curator, Zoological Institute for Recently Extinct Species

A project by

Jozef Wouters

In collaboration with

Menno Vandevelde, Bart Van den Eynde, Celine van der Poel, Karolien Derwael (Klein Verzet), Leen Hammenecker, Christophe Engels (Bluebird Conspiracy), Tim Vanhentenryck, Hanne Van Den Biesen, Joleen Goffin

Thanks to

Scheld’apen, Vladimir Miller, Jorge Luis Borges, Stefan Moens, Freek Vielen, Rebekka de Wit, Wannes Deneer, Michiel Vandevelde, Elsemieke Scholte, Willy Thomas, Lila John, fABULEUS

Sponsored by

Gigant

Presentation

Kunstenfestivaldesarts, KVS, Muséum des Sciences naturelles/Museum voor Natuurwetenschappen

Production

mennomichieljozef vzw (Leuven)

Co-production

Kunstenfestivaldesarts, KVS (Brussels), Muséum des Sciences naturelles/ Museum voor Natuurweten schappen (Brussels), detheatermaker vzw (Antwerp)

Supported by

Vlaamse Overheid

This project is part of

Tok Toc Knock 2012-2013 (city project by KVS)