11.05, 12.05, 14 — 17.05.2008

Amir Reza Koohestani / Mehr Theatre Group Tehran

Quartet : A Journey to North

theatre

Farsi → NL, FR | ⧖ 1h20

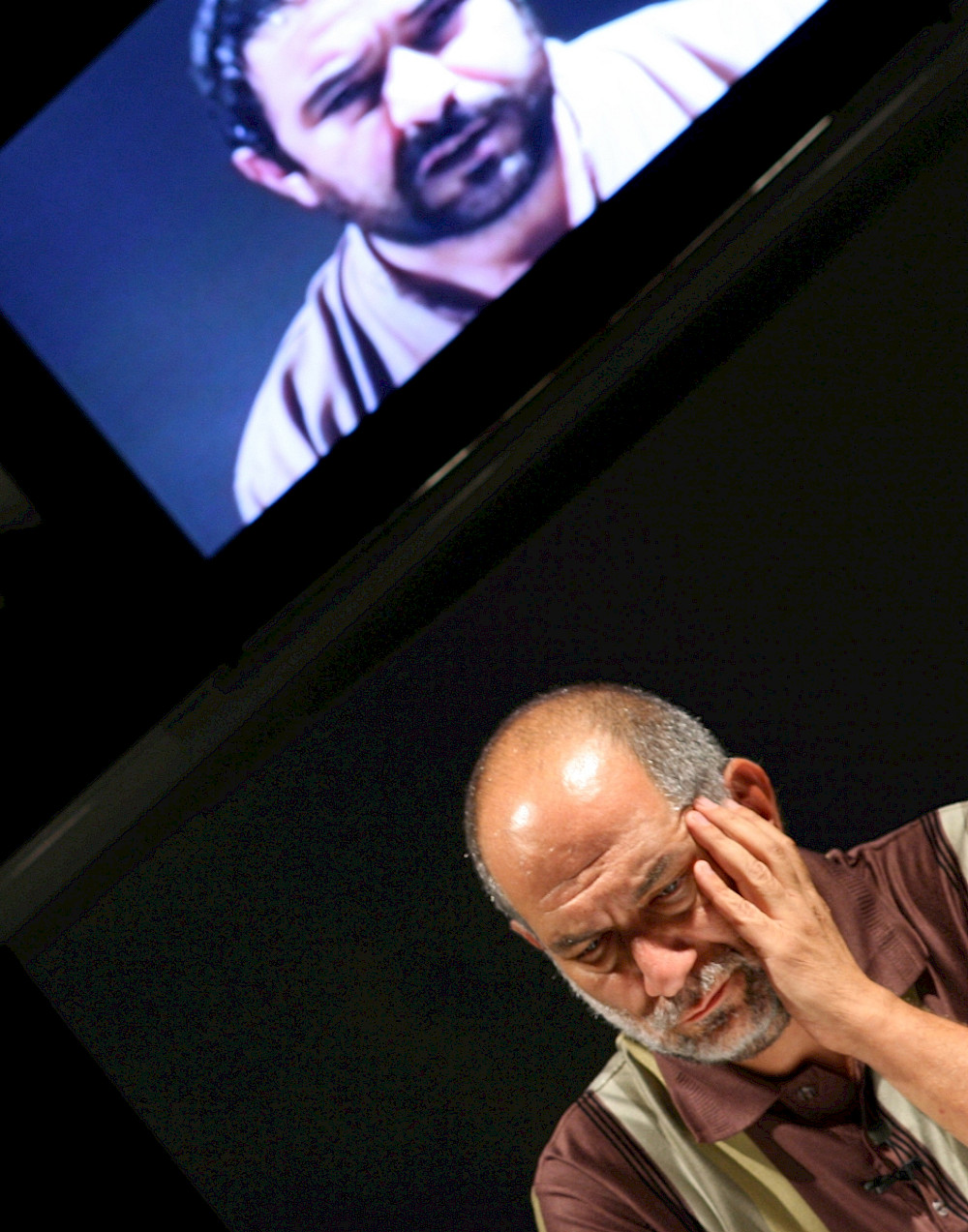

Since Dance on Glasses (kfda 04), people have been aware of Amir Reza Koohestani's talent for tackling political issues using poetic and allusive forms. The Iranian has honed a theatre of face-to-face encounter, where minimalist staging serves the words, the language and the acting. His new production, Quartet: Journey to North, is based on the real story of two Iranian murderers: a customs official who massacred several members of his family, and a well-off teenager who took her fiancé's life. With their backs to the centre of the stage, four actors directly address the audience seated around the stage, offering four interwoven accounts from the two murderers and two relatives of the victims. A television screen above each actor allows the other actors' faces to be seen: with movement passing from the world to the stage, and then to the screen. A documentary stage installation that takes us deep into the motivations of the human mind.

Amir Reza Koohestani and Quartet

Working technique

Artistic collaborations with Amir Reza Koohestani are defined by constant flux. It is precisely this trait that threatens to reduce anyone who is participating in the performance – producers, actors and technicians – to despair. At any time during the creation of a piece, Koohestani may destroy the entire composition and begin anew.

He begins his rehearsals with two or three monologues, and additional text is written for the first time during the rehearsals. Following completion of the text, he returns to the initial monologues and rewrites the original scenes. The actors know the first part of the play, but they don’t know which direction the play is heading in. Consequently, their initial conceptions of the characters must be adjusted based on later developments.

The rehearsals for Koohestani’s plays are carried out in absolute silence. He never interrupts the rehearsals; the actors are allowed to complete entire scenes without interruption. Koohestani writes down any critical points that he might have and discusses these in private with each of the actors after the rehearsal. Consequently, his rehearsals are so quiet and focussed that they can be likened to a religious ceremony.

Historical background on contemporary theatre in Iran

Today, the political system dominates the cultural and artistic conditions in Iran more than it does in other countries. During his years in power, Mohammad Reza Shah financed the Shiraz Art Festivals with a large portion of the national income. At these festivals, a good number of internationally well-known theatre directors like Brook, Grotowski and Wilson staged plays whose high production costs were covered by the Persian State. The Shah did this because he wanted to transform Iran’s image into that of a modern, developed society. However, up to this point only traditional forms of theatre, like Taazieh and Siah Bazi, were accepted and well-liked by the Iranian public.

Most performances of works by Western playwrights such as Shakespeare, Chekhov and Ibsen were based on texts that were poorly translated by Iranian foreign students, and these lacklustre texts were staged by theatre groups with little knowledge of contemporary trends in theatre.

By order of the Persian court, avant-garde theatre of the late sixties was forced upon the local artistic community. This brand of performance was incomprehensible to the general public and was incapable of surviving without public funding. Consequently, theatre developed into an art form that narrowly targeted a specific stratum of intellectuals. The State supported numerous avant-garde and experimental plays, while independent Marxist and anti-Shah groups worked, in defiance of the strict censorship, without State support on plays with strong political content.

The Iranian revolution of 1979 brought with it numerous artistic prohibitions. Amidst the chaos of the revolution, there were, on the one hand, those artists who had been supported by the State in the time of the Shah and who were labelled royalists and, on the other hand, a group of embattled artists who, as a result of their Marxist beliefs, were considered communists and atheists by the new ruling class. Those who were not thrown in jail either fled the country or committed suicide as a result of war-induced depression and psychological pressure.

As a country embroiled with a war with Iraq and suffering from an American economic embargo, Iran could not provide adequate funding for cultural activities. At the beginning of the 1980s, Iranian theatre was first and foremost a propaganda tool for religious themes. The State funded performances that were designed to attract as large an audience as possible. To avoid censorship, the few independent writers and directors worked on plays with mythological and symbolic content, which was light years away from the everyday experiences of Iranians living through an eight-year war. The population was too preoccupied with its own livelihood to find time for the theatre, and theatre performers turned their attention to film work, which could at least satisfy their financial needs.

In 1997, nine years after the war ended, Mohammad Khatami was elected president. He stepped onto the political stage beneath a banner of “cultural development and democracy” and – for the first time since the revolution – spoke about ancient Persian culture and civilisation. The State had previously considered Persian civilisation, based on its pre-revolutionary use by the Shah, merely a legacy of past regimes and suppressed it. When Khatami came into power, theatre performers returned to the halls again. Censorship dropped dramatically and the everyday problems of the population replaced symbolic and mythological content. Many new theatre groups formed, including the Mehr Theatre Group from Shiraz.

The Mehr Theatre Group’s vision differed markedly from the notion of performance held by most critics and theatre people in the town of Shiraz, located 900 km south of Tehran. Concentration, silence and analysis of Western movie actors from the 60s and 70s dominated this group’s rehearsals. (In light of the various political and economic embargoes, the only sources of inspiration at this time were illegal copies of films by European and American filmmakers like Scorsese, Bergmann and Wajda.) Mehr’s self-willed performance style, which stemmed from its actors’ youth, lack of experience and distance from the prevalent theatrical trends in the capital city, manifested itself strongly in the first plays that it staged. The group also benefited from the use of a well-equipped theatre in Shiraz for one year at no cost.

Theatrical work

Like many of Mehr’s early performances, the staging of Amir Reza Koohestani’s first play, A Murmured Tale (1999), had a realistic setting. (Members of the group would come to distance themselves from theatrical realism). The realistic action in Koohestani’s later plays contrasts sharply with the surrealism of the stage design and the texts.

Stage design is a major element in Koohestani’s work. In general, he develops the stage design first and then writes the play. In Dance on Glasses (2001), a play about the relationship between a girl and a boy, the actors face each other at a four-metre-long table. In arranging the actors this way, Koohestani demonstrates the impossibility of true communication and attempts to produce characters and dialogues that correspond to the motionlessness and silence on the stage. During the performance, the members of the audience sit like the characters on the stage, in two groups divided according to gender. Though the two groups might appear complementary, they are incapable of communicating with each other. In his plays, audience members sit close enough to the stage that they can hear the actors whispering; they become voyeurs secretly observing the loneliness of the characters. This is especially noticeable in the plays Dance on Glasses, Recent Experiences and Quartet.

The impossibility of communicating is addressed differently in his later plays. In Single Room (2006), a mother and her dead son talk about their problematic relationship, but neither can hear the other.When the characters in Amid the Clouds (2005) want to talk about their secret feelings and views, they turn away from the seated actors and speak to the audience. In Dry Blood and Fresh Vegetables(2007), which consists of a single, long, uninterrupted telephone conversation between a mother and her daughter, the characters pass by without seeing one another. While the characters in most of Koohestani’s plays sit quietly, the characters in Dry Blood are always moving. In Dance on Glassesand Quartet, their lack of movement hints at their shared shame. They do not ask to sit, they presumably lack the strength to stand.

Koohestani’s texts are extremely realistic. He does not try to impress the audience with his verbal acumen; rather, he uses everyday language and even purposely writes incorrect sentences. During the creation of Quartet, for example, he occasionally changed dialogue that he felt was too complete, correct or clean.

Text

Amir Reza Koohestani, Mahin Sadri

Direction/Stage& costumes / light design

Amir Reza Koohestani

With

Attila Pessyani, Mohammad Hassan Madjooni, Baran Kosari, Mahin Sadri

Sound design

Ankido Darash

Video

Hesam Noorani

Production manager

Mohammad Reza Hosseinzadeh (assist.)

Production

Mehr Theatrical Group

Coproduction

Wiener Festwochen, Festival Theaterformen (Braunschweig), Holland Festival (Amsterdam), Kunstenfestivaldesarts

With the support of

Dramatic Arts Centre (Tehran)