27 — 31.05.2025

Gabriela Carneiro da Cunha São Paulo

Tapajós

theatre

| Portuguese, Munduruku → FR, NL, EN | ⧖ 1h30 | €18 / €15 | Contains strobe lighting effects

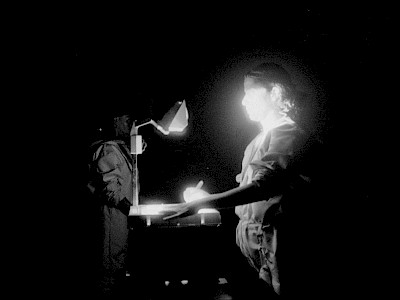

Developing an analogue photograph is like alchemy, making existences magically appear and disappear. In photography’s early days, the development process required the use of the same chemical element responsible for the destruction of the Tapajós River and so many of its inhabitants: mercury. Gabriela Carneiro da Cunha, an exciting new voice in the international theatre scene, is engaged in a long-term artistic study of the ravaged rivers of her homeland Brazil and the women living on the Tapajós' banks, fighting to heal their bodies, wombs, children and their river.

Tapajós is born out of an encounter with mothers polluted by the Tapajós River, poisoned by mercury from illegal mining activities. This performance has since become an alliance of mothers: the Munduruku mothers, the fish mother, forest mother, river mother and, finally, the mothers in the audience.

Using trays of water and photographic chemicals to develop pictures, aided by the audience, Carneiro da Cunha creates a performance where emerging images guide a narrative about the river water, about pollution and photography as a form of testimony. The words and bodies of the women and the river combine in a vivid, fervent investigation, with the audience as chorus and instruments of the performance-ritual, helping to link the visible with the invisible world.

Interview with Gabriela Carneiro da Cunha

Vincent Théval – Your new creation, Tapajós, is part of the Riverbanks Project On Rivers, Buiúnas and Fireflies cycle. What does this project cover?

Gabriela Carneiro da Cunha – It’s an artistic response to what is called the Anthropocene, the Capitalocene or—to use the words of Davi Kopenawa Yanomami—“the revenge of the Earth”. It is a piece of long-term research, devoted to listening to rivers facing a disaster. We have been working on it since 2014, and so far have listened to three rivers: the Araguaia, whose testimony relates to the women who fought and died at the time of a major guerilla struggle, during the dictatorship in Brazil; the Xingu river, whose testimony about the building of the Belo Monte dam we have heard; and now, the Tapajós river, which evokes the mercury pollution during illegal mining operations.

Over more than ten years, I have learned about and promoted the idea that each river is a language and not a topic. The aim was to gather the testimony of a non-human being, and it has driven me to develop my listening capacities. In this process, time is a valuable ally. A river can be an excellent story-teller, if you give it the time, and if you take the time to listen to it. Each one needs around three years’ work.

The writing of Tapajós essentially relies on two events that you attended: the Mercúrio assembly, and the Sairé festival. How did you navigate these events, and how have they shaped your creation?

The listening process on the ground began in 2022, when with Vicente Otávio and Carolina Ribas, I went to the Mercúrio assembly in the Munduruku territory of Sawre Muybu. On this occasion, the results of the mercury pollution research carried out by Dr Paulo Basta of FIOCRUZ—a major Brazilian health institution—were presented to the Munduruku people. Even though they already knew that they were contaminated, since they could feel the effects of it in their bodies, they were aware they had to rely on scientific research expressed in the language of the Whites, if their accusations were to be taken seriously. Confirmation of the contamination was a difficult moment, since the long-term effects are terrible. It is especially serious for pregnant women, who contaminate their own children through the amniotic fluid and then through their milk. This is a tragedy.

After the results were announced, the Munduruku women took the microphone—sad and angry—and one of their leaders, Maria Leusa Munduruku cried out that they were fighting for “their sick land, their sick river and their sick wombs”. This gave the work a maternal dimension: listen to the mothers, whether or not they have borne children.

Immediately after this assembly, we went to Alter do Chão. This part of the river also has high levels of mercury, but it is further away from the mining activities. We arrived at a time of celebration: the Sairé festival is a meeting of worlds—Catholic and indigenous Borari—where each of the two cultures has its own place and its own practices. It is one of the most beautiful and vibrant celebrations in Brazil. It proved to me that a meeting between cultures is possible, from the moment each one preserves its own integrity. I also understand that—on the riverbanks as elsewhere—struggle goes hand in hand with spirituality.

When I discussed with Ediene Munduruku how to care for the Tapajós river, she explained to me that we have to work with the mother of the river. Hence, the work took the form of a multi-species alliance between mothers: the Munduruku mother, the mothers of the audience, of the Tapajós, of the fish, the mother of the forest, and whoever has the experience of “becoming mother”, even without wishing to have children.

Women hold a central place in the Riverbanks Project, as they do in the resistance movements in Amazonia. Do you feel close to eco-feminist thinking?

The project hinges on three axes: listening to the waters, listening to the Buiúnas women 1, listening to human and non-human creatures. Create with them. Compose with them. Enhance the language and the theatre with them. Buiúna is a half-woman, half-snake figure, and listening to the Tapajós women also meant listening to the entity that they bear: the mother of the river. Mothers are also those most affected by the pollution, and it is they who are leading this fight, even though they are not alone. This central role is very practical, not theoretical. I love theory, but I am more a part of my personal relationship with them and with the waters.

What you saw down there is made present on the stage thanks to photography. How did you adopt this medium?

I followed on the trail of mercury, a chemical element essential to life, which led me to photography, since it was used in the earliest days of this medium. The problem is not mercury itself, but rather its use. So, to paraphrase the philosopher Donna Haraway, it’s a matter of how to compose using the world’s materials. This interests me more than finding a cause. This agent—mercury—has brought me its own cosmology, of which photography is a part, as are mining operations. The same chemical products can make existences disappear and make them appear, depending on how they are organised. Besides, we should not forget that production of an image—analogue or digital—needs minerals that come from the earth. Creating an image is therefore also a matter of life or death. In the process of working with analogue photography, we have also experimented with the alchemical and magic aspects of this technology, which dialogue with elements of the Riverbanks Project, and of Tapajós in particular.

What place does spirituality hold in Tapajós?

Spirituality, beliefs and rituals are technologies which enable listening, seeing and dreaming. Art is also one. So is theatre.

- Interview conducted by Vincent Théval in April 2025 for the Festival d’Automne à Paris.

- Translated by Joanna Waller.

- Vincent Théval is a radio producer, and writes articles about culture for the press.

1 Gabriela Carneiro da Cunha is referring to the Buiúnas network, whose aim is to bring together women who share the common goal of protecting the health and life of Amazonian rivers. The network is made up of twenty-four women artists, journalists, anthropologists, prosecutors, university professors, environmental activists, psychiatrists and others.

Presentation: Kunstenfestivaldesarts, Les Halles de Schaerbeek

Conception and direction: Gabriela Carneiro da Cunha and the Tapajós River | Performers: Gabriela Carneiro da Cunha, Mafalda Pequenino | Creation in process: Sofia Tomic, João Freddi, Vicente Otávio, Mafalda Pequenino, Gabriela Carneiro da Cunha | Assistant director: Sofia Tomic | Photographs: Gabriela Carneiro da Cunha, João Freddi, Vicente Otávio | Photography technicians: João Freddi, Vicente Otávio | Text editing: Manoela Cezar, Gabriela Carneiro da Cunha, João Marcelo Iglesias, Sofia Tomic | Image editing: Gabriela Carneiro da Cunha, João Freddi, Marina Schiesari, Sofia Tomic, Vicente Otávio | Dramaturgy: Alessandra Korap, Maria Leusa Munduruku, Ediene Munduruku, Cacica Isaura Munduruku, Ana Carolina Alfinito, Paulo Basta, Julia Ferreira Corrêa, Rosana Farias Mascarenhas, Dalva de Jesus Vieira, Osmar Vieira de Oliveira, Celiney Eulália de Oliveira Lobato, Rodrigo Oliveira, Mauricio Torres, Eric Jennings | Munduruku–Portuguese translation: Honesio Dace Munduruku | Technical direction and lighting: Jimmy Wong | Lighting Assistant: Matheus Espessoto | Sound design: Felipe Storino | Costume design: Sio Duhi | Scenography: Sofia Tomic, Ciro Schu, Jimmy Wong | Exhibition design: Marina Schiesari | Consultancy: Raimunda Gomes da Silva, Dinah de Oliveira, Tomás Ribas | Sound technician and multimedia design: Bruno Carneiro | Associated Production: Associação de Mulheres Munduruku Pariri, Associação Sairé | Support and partners: Associação Fotoativa, Clube do Analógico | Production: Ariane Cuminale | General production: Gabi Gonçalves | Distribution in Europe: Théâtre Vidy-Lausanne

Production: Corpo Rastreado, Aruac Filmes, Théâtre Vidy-Lausanne, Projeto Margens | Coproduction: Kunstenfestivaldesarts, Les Halles de Schaerbeek, Wiener Festwochen, Festival d'Automne à Paris, Centre Pompidou, La rose des vents/NEXT Arts Festival, Théâtre Garonne, Kampnagel International Summer Festival

With the support of Manchester International Festival for research & development of the project