14.05, 15.05.2025

Using mesmerising videos, sculptures and complex historical reconstructions, Wael Shawky raises questions about the ambiguities of documentary records, and the authority of written history. His latest work, Drama 1882, was a highlight of last year’s Venice Biennale.

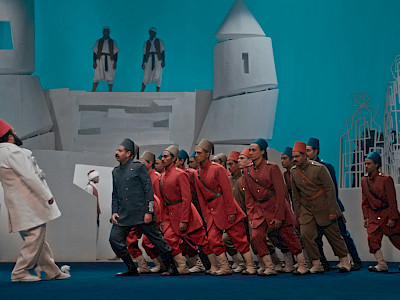

The eight-part operatic film reconstructs the moment of Egypt’s nationalist Urabi revolt against colonial rule (1879-1882). Colonel Ahmed Urabi, who rose through the ranks from his peasant origins to found the Egyptian Nationalist Party, led the uprising and campaigned to secure Egypt for the Egyptians. But what exactly happened in 1882 to implode his popular movement, precipitate a full-scale bombardment of Alexandria by British forces, and his subsequent exile?

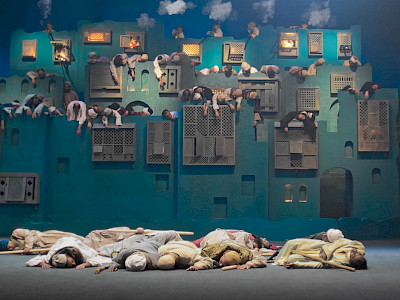

Filmed in a historic theatre in Alexandria, and set against a backdrop of striking, painterly sets, Shawky directs his cast with precision in a magical, theatrical musical. The characters move in a slow, hypnotic choreography, they sway like plants immersed in the current of a river. The word ‘drama’ has many implications: it conjures a sense of entertainment, the sense of catastrophe and our inherent doubt in history. A timely and critical conversation about the necessity of revisiting history and the futility of war.

"The Egyptian artist once again revisits history in his own epic, serious and whimsical way." - Emmanuelle Jardonnet, 2024, Le Monde

"Egyptian artist Wael Shawky creates a scientific body of work that examines collective mythologies." - Colin Lemoine, 2024, Connaissance des Arts

“The XIXth century is a strange century because European inner empires start to fail, very slowly but surely, while Europeans start the colonial empires established by the French, British, Dutch, Belgians, in all of Africa and big big chunks of Asia, if not all of it. Here, there are liberation movements, while there, in the same time, other peoples are being brutally submitted.”

(Etel Adnan, About the end of the Ottoman Empire, 2015)

Chronicles

Friday morning, September 9th, 1881. A young Egyptian army colonel by the name of Ahmed Urabi leads his nationalist command troops into central Cairo towards Abdeen Palace, where he surrounds the residence of Khedive (1) Tewfik. Tensions have been simmering all summer. Egypt’s economy is in plight, and under the pretext of protecting creditors’ rights, Great Britain’s heavy hand in local affairs has sent rumbles of discontent through society. Corruption is rife, and there is growing sentiment among Egyptians that national resources are being pillaged, and countrymen undermined. Outside the palace, Urabi leaps upright onto his horse’s saddle, bears and raises his sword, and demands that the British-backed Khedive yield to pressures for reform. Calling for the establishment of a parliament, an enlarged army, and the removal of the Ministry of Riad Pasha, he declares: “We come to offer the requests of the entire army and whole nation!” The Khedive replies with confrontation, “I inherited the kingdom of this country from my fathers and grandfathers and you are only our slaves!” Urabi challenges him, “we will not be inherited and will not be enslaved from now”. Tension ensues. The Ministry falls. Urabi stands defiant.

It is the events of this September day that set into motion the British bombardment of Alexandria less than twelve months later, in an urgent attempt to overthrow the new nationalist guard and reinstate the powers of the Khedive and imperial grip. It was also to this backdrop that a slender book entitled Risãlat al-kalim al-țamãn (‘Essay on Eight Words’) was published just weeks after the palace stand-off. The book was written by Ḥusayn al-Marṣafỉ, a senior professor at Dar al-Ulum, which had been established a decade earlier to produce teachers for the new government, and in essence his writing reflected the pulse of the moment. The volume was quite literally a discussion of the meaning of eight words “currently on the tongues of the younger generation today”. They were: nation, home- land, government, justice, oppression, politics, liberty, and education. As the scholar Timothy Mitchell notes in Colonizing Egypt, Urabi’s ideas about political machinations had largely been formed through military manuals prepared for the French, and what al-Marṣafỉ was addressing in his book was a political crisis that in his view grew out of a misuse and misunderstanding of words. Egypt needed its own system of education, and its own vocabulary and set of defined terms. This thinking extended to every facet of the idea and ideals of a sovereign state. This was what Urabi’s troops would fight for.

*

“We are all like marionettes, manipulated by forces we cannot see.” He allows the strings to be obviously visible in the films: every step and speech is controlled by a higher power—God perhaps, or the historian, or the artist. But the gravity-defying marionettes have a life of their own; their movements are never fully under the puppet-masters’ control. They are free and unfree at the same time: in other words, disconcertingly human.

(Sameer Rahim, about the Cabaret Crusades Trilogy, apollo-magazine.com)

For more than three decades, the Alexandrian-born artist Wael Shawky has blurred and redefined boundaries between film, performance, sculpture and installation through works that intervene in the gaps of the mostly widely-held historical accounts of the culture and history of Arab world. His multi-layered films and installations entail intricate hand-made sets and period costumes, as well as puppets, marionettes, and both trained and untrained actors, including children.

Set alongside sculptures and drawings, his work immerses rigorously-researched accounts of history into worlds of his own creation. This mix of truth and fiction posits his practice. He premises history to be a record of subjectively depicted sequences rather than indisputable facts. Through elaborate reconstructions of historic events, Shawky re-evaluates and raises questions about the ambiguities of chronicled documents of record, and the authority of written history.

- Yasmine El Rashidi

Projective imagination

To consider Shawky’s work, one can turn to the analysis in The Atlas of Emotions by Giuliana Bruno: “An architectural imagery is an active visual deposit: it is an archive open to the activities of excavation, re-visioning and re-envisioning

in art. In these urban archives, doors are always open to the possibility of reimagining space, and archeology here is not simply about returning to the past; rather, it allows us to look in other directions, and especially towards the future,

in an active retrospective movement”.

But the records are not limited to what happened. They are made up of various image-creation trajectories. This construction is based on the inseparable nature of vision and travel. In an evocative montage of words, songs and images, the artist immerses the viewer in the posture of the voyeur, who must also be the traveler.

Shawky belongs to a particular family of artists who create atmospheres through film. What do atmospheres allow? How do they help create a visual environment? The artist reinvents projective imagination according to atmospheric thinking, in an approach which confronts the notions of projection and atmospheres as they have been formu- lated in other fields (the sciences, humanities, philosophy, history, and so forth). He has developed a unique artistic writing style that allows him to move freely between fiction, documentaries and historical events.

Shawky is a pioneer in the development of a new cinematographic writing which expands the spatiality of the film form. To do so, he engages in the broader field of film installation. This way of working allows him to navigate between mediums to construct a work of totality: the sets, the scenario, the direction, the music. Whether in theatrical form or through installations, he always considers the screen as a porous material, which serves as a supporting structure for an intense projection experience. The screen is a place of transition, of passage. The screen allows everyone to access the intimate character, but also the life of the other, which is played out before our eyes. He delicately constructs fluid geographies—landscapes of images of places (Alexandria, Istanbul, the Suez Canal...). Sometimes these territories become the portrait of the city. Long-held shots, like the slow movement of actors, allow the effect of extending duration, letting the location speak for itself. We are given access in this way to the internal logic of the experience of movement and change. The fixity of the plans keeps our attention sharp. We empathize with the scenes playing out before us, and so we are not distanced from the story. On the contrary, the scene that takes place “there” then becomes an active “here”. This story can no longer be foreign to us because the chain of humanity links us to each other.

- Sebastian Delot

(1) A title equivalent to that of a viceroy, granted by Sultan Abdülaziz to the Pasha of Egypt Ismail (1867), encompassing sovereign privileges. This title was held by Ismail’s descendants until 1914. (Source: larousse.fr)

Presentation: Kunstenfestivaldesarts, Albert Hall Brussels

Director, production designer, costume designer, original score: Wael Shawky | Screenplay: Wael Shawky, Islam Salama | Director of photography: Mina Nabil | Editor: Mark Lotfy | Sound: Michael Fawzy | Sculptural team: Kain Walgrave, Giorgio Benotto | Installation team: Ibrahim Salama, Daniele Rancilio, Federico Elia, John Mirabel, Ikra Costruzioni | Audio-visual and light installation: Eidotech | Choreographer: Mirette Mechail | Theatre executive director: Ahmed Shawky | Film executive director: Abanoub Nabil | Theatre assistant director: Mohamed Farouq Rocky | Musical arrangement: Mohammed Hosny | Vocal supervisor: Mohammed Khaled | Recordings songs, mixing and sound design: Michael Fawzy | Costumes supervisor: Nahla Morsy | Scenography supervisor: Osama Gaber | Historical writing and proofreading: Islam Salama | Project manager: Giorgia Rea | Executive manager: Antonio Zanon | Press office: Evergreen Arts | Graphic designer: Mona Zanana | Production implementation: Ahmed Sayed | Fundraising: Mai Eldib

Production: Mass Alexandria | Theatre executive producer: Osama Al-Hawary | Film and theatre producer: Mark Lotfy | Production companies: Wael Shawky, Mass Alexandria, Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Lisson Gallery, Lia Rumma Gallery, Barakat Contemporary

The glass work would not have been possible without the help of Adriano Berengo, Berengo Studio | Thank you to the gallery teams: Ana Siler, Lina Kiryakos (Sfeir-Semler Gallery), Giulia Tassinari, Maud Greppi (Lia Rumma Gallery), Claus Robenhagen, Victoria Mitchell (Lisson Gallery), Yunu Lee (Barakat Gallery) | Additional thanks to: Annamaria Alois, San Leucio (Velvet Fabrics), Fonderia Nolana (copper plate), Ambassador of Italy to Egypt Michele Quaroni and his wife Veronika, Marwan Elshazly and Panmarine Logistics, Dr. Waleed Kanoush (Head of the Fine Arts Sector, Ministry of Culture, Egypt), Ahmed Kamal Eldin (Director-General of National and International Exhibitions, Ministry of Culture, Egypt)