29.05 — 01.06.2024

The encounter between Marlene Monteiro Freitas and Israel Galván seemed destined to happen. It's as if an invisible thread runs between the Cape Verdean choreographer and the Sevillian dancer. At one end is Monteiro Freitas, well known to previous festival audiences, whose choreography combines extreme precision and freedom, mechanical movements and expressionism. At the other end is Galván, one of the world's best-known flamenco dancers, whose trademark rapid-fire footwork is punctuated by stillness and silence. They had long wanted to bring their two seemingly distant worlds together, united by a passion for rhythm and the ability to combine tension with fiery expressiveness. They are on stage, a wall behind them, inescapably exposed to the audience. Facing each other, they weave a new – and yet immediate – communication: a grammar composed of choreographic steps, snappy gestures and sudden interruptions. They interact like creatures getting to know each other, mixing challenge and seduction in an arrangement that might echo a bullfighting dance. Daily improvisation keeps the dialogue alive. It is a breathtaking encounter between two incredible artists, a moment of pure joy and humour, an animated conversation using only the language of the body.

Dissimilar twins

RI TE by Marlene Monteiro Freitas & Israel Galván

A ritual is involved, but it’s split. There’s a show, but it’s merely an intermission. For what? For something you cannot see, but is happening elsewhere, off stage, another show that this show is interrupting, a fever that starts subsiding before flaring up again. Unless it’s just about the day of the two protagonists who have ended up on a theatre stage by chance. The set is minimal: a wooden floor in front of a wall flanked on either side by a narrow wall and a neon light flickering above two empty chairs, attributes of flamenco dance, creating both a stage and an office – in fact a box that is opened while the show is on and that you imagine will close on the two devils when it’s all over. The rest of the stage is in the dark. If you want to be seen you have to be right there, under the neon light, occupying the space, encountering the other person there.

So RI TE is the story of an encounter. The encounter between Marlene Monteiro Freitas and Israel Galván. The encounter between the Spanish master’s flamenco novo and the unpredictable and metamorphic dance of the Cape Verdean choreographer. It’s an encounter because each of them is coming just as they are, bringing with them what they know how to do; there’s no question of starting from any form of common ground worked out in advance or having any kind of improbable synthesis of styles. The two syllables in the title will stay separated.

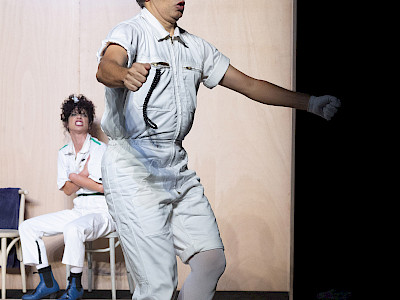

And yet the two characters wandering from one part of the stage to another as the audience take their seats seem to be a reflection of each other. They make almost the same movements, have the same uptight look, and wear artfully dissimilar clothes (differentiated in their details). They’re like twins who are cultivating their differences but can’t help imitating each other. The Christmas carol (Stille Nacht) gently playing emphasises the sweet monstrosity of the stage. Is it the rite’s role to reconcile these two bodies? Cancel out their differences? Or meld their weirdnesses? Another way of interpreting the separation of the syllables in the title.

This show, which isn’t really one at all – tells a dual story: about two bodies that, despite their differences, are trying (and learning) to dance together and about twins who balk at accepting their similarities. Hence these opposite movements that can’t stop coalescing: they show themselves/they hide, they move closer/they move apart, they attract/they repel. The parade that opens the show produces a series of such movements. They start by hiding (which is tantamount to disappearing). When they come forward, it’s to show themselves – performing a dance step, a wink, a gesture of disdain – before immediately returning to the shadows. Then, at last, they’re face to face. Each on one side of the stage, haughtily chewing gum, chins up, chests out. They adopt poses, place a foot on the wooden floor before immediately lifting it again, embark on brazen llamadas. They brave each other’s gaze but at the same time are restrained. They’ve barely started before the gesture is interrupted. The effect is comical, like any movement that stops suddenly and catches the body out. Taken to the extreme, the process turns them into automatons who have to wind up their mechanism again whenever they can.

There’s one extraordinary moment in this regard. After the parade, they’ve gone back to the office-box, sat down and danced together, each on a chair, striking their feet and hands in imperfect synchrony, then the ritual is completed. The ritual can change from one performance to the next, but it always features the same two elements: saying “Olé”, bringing it up out of their throats because it’s what suffocates and blocks the body and prevents it from acting; and responding to a gesture with the opposite gesture, for example responding to a gesture of love (from one) with one of disgust (from the other). There’s nothing psychological in it, it’s just the physics of affects.

After the ritual is over, the moment comes. She catches him and he starts dancing like Petrushka in Stravinsky’s ballet. Marlene Monteiro Freitas catches Israel Galván except that they’re no longer Marlene and Israel, but two puppets connected by invisible strings. She’d be the puppeteer if she weren’t a puppet automaton mechanically performing all her movements herself. On the one hand a puppet pulling another puppet’s strings, and on the other a gesture of love producing a gesture of disgust. In other words, there are two principles in this show-intermission: the mechanical body and the contrariness of gestures. Which explains why there’s plenty of laughter until the very end.

As Marlene Monteiro Freitas’ repeated “Olé” reminds us, it’s about dancing the flamenco. Until you become stupid. It’s less about dancing it, though, than exhausting its codified lexicon, the hallmarks of its style, the gestures, the looks, the positions, the set, everything that indicates this art form without being it, the flamenco without the duende, pieces of the flamenco, the flamenco-idiot. The only zapateado we’re allowed is tapped in rubber boots and stops midway through. Israel Galván is one of the masters of detached body movements, pulling them apart and putting them back together differently. With Marlene Monteiro Freitas, it takes on a different dimension. The flamenco is no longer a dance, it’s an absurd movement that grabs hold of the bodies, turns them into puppets, thwarts their gestures, is passed from one to the other like a sudden fever or a violent wind. It is the “Olé” that remains stuck in the throat or this slightly affected gesture of love that is met by a slightly too ostentatious gesture of disgust. If there is any duende, it can only happen through an intrusion, unintentionally, less an excess of art that an absence of it. The duende is the grace that comes to idiots when they allow a movement that has come from elsewhere to pass through them and carry them away.

- Bastien Gallet, April 2024

Bastien Gallet is a writer, teacher and editor. He writes fiction, essays, opera librettos and screenplays. He teaches philosophy. He runs the publisher MF. He is a critic for the online magazine AOC. He is part of the Panamérica Transatlântica carnival block and the Laboratory of Pirate Ecology.

Presentation: Kunstenfestivaldesarts, Zinnema

Concept and performance: Marlene Monteiro Freitas & Israel Galván

Coproduction: Théâtre de la Ville, Festival d’Automne à Paris

Performances in Brussels with the support of the Spanish Embassy in Belgium