10 — 12.05, 14.05, 15.05, 17 — 19.05.2019

François Chaignaud & Marie‑Pierre Brébant Paris

Symphonia Harmoniæ Cælestium Revelationum

music / dance / exhibition — premiere

⧖ 2h30 | € 18 / € 15

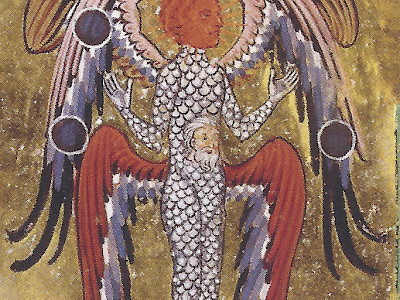

Symphonia Harmoniae Caelestium Revelationum is the title of the musical oeuvre of Hildegard von Bingen, the twelfth-century Benedictine abbess, mystic, theologian, physician and musician. François Chaignaud and Marie-Pierre Brébant invite the audience to immerse itself in her complete cycle of 69 monodies during a three-hour session. They recite the songs from memory, accompanied by the bandura, a traditional Ukrainian string instrument. Their bodies form a musical archive which, song after song, confronts us with another perspective on the roots of Western culture. The work of Hildegard von Bingen is characterized by the use of keys that can easily sound strange with regard to the European musical tradition. Chaignaud and Brébant give voice to the unexpected tonal anomalies that once formed the core of Western culture but have now vanished from the modern canon. Their exploration of our musical and spiritual past straddles the border between a meditative installation, a concert and a contemplative choreography. Body, voice and bandura culminate in an ecstatic vision that exposes once more the physical relationship with the divine.

See also: Free School: Medieval Singing Class

To listen: Symphonia Hildegardia, our four podcasts about Hildegard von Bingen, initiated by Symphonia Harmonyæ Cælestium Revelationum. Listen to the 4 episodes hereunder or on SoundCloud (in French).

Hildegard: Time in its entirety

Almost a thousand years have passed and everything Hildegard of Bingen achieved is now opaque, mysterious and fascinating to us.

This woman – made a saint in 2012 – no longer appears other than beneath successive masks: the nun, the botanist, the visionary, the musician, all shifting reflections whose contours are a struggle to make out. Yet Hildegard was a real person of flesh and blood, a living being with relations. We know the dates of her birth and death, there are documents that bear witness to what she experienced, and we can still handle pages today that were once touched by her fingers. But Hildegard is also a character from fiction, a creature-creator in whom we have placed our desires and projections over the centuries.

The abbess’s work has the disarming beauty of a mystery, one all the more profound because we are unaware of whether it is a product of our ignorance or of its author’s genius. The traces she left us can only be approached with utmost humility: while historical science allows its outlines to become clear, her work can only ever be confronted in the obscurity of direct, unfiltered influence.

For a number of years Marie-Pierre Brébant and François Chaignaud have been unravelling the two twelfth-century manuscripts that contain all the music attributed to Hildegard. Fascinated by this homogenous archive, they have studied it for what it is: a long score that they have followed step by step just as you follow a footpath you stumble across. They learned to decipher its hybrid notation – a blend of modern staves and neumes – in order to be able to read it. A detailed study, gradually and relentlessly exploring its modality, ornaments and melismas, has allowed them to absorb the worlds documented by these scores: a rural world bathed in sounds and song, a magical world interspersed with Orphic links and filled with cosmic aromas, a monastic world of rules, renunciation and ambitions.

Hildegard started writing Symphonia harmoniae caelestium revelationum in the 1150s. She was fifty years old and her visions had recently been acknowledged as true by Pope Eugene III and he had given her the task of compiling them into a book. She left Abbot Kuno’s community to establish a convent for single women on a hillside close to Bingen. Alongside the work to construct the new monastery and publish Scivias, she embarked on creating an imaginary language, composing a musical drama and undertaking lengthy correspondence. She also collected hymns and sequences created for church services. Eugene III enjoined her to write and Hildegard speedily complied, going beyond the strict confines of her gift as a visionary.

She was a woman who was aware of her power and who chose to make liturgical singing a matter of posterity, devoting the same care to her music as she gave to hagiographies and revelations, taking us a long way down the river of time so that today we can listen to words and melodies uttered in times past by bodies of which nothing, not even a memory, remains.

While Hildegard’s intention might be unclear, her work has reached us intact. What this music says through its poetry, its tension and its form speaks to us again, and particularly challenges the present day and our customs: all we have to do is listen.

These signs come from a closed and organised world, a world whose complexity is not based on human ignorance but on divine ineffability. The mission of man is not yet to clarify root causes – his efforts at understanding are directed solely to the relationship between the physical, imaginary and spiritual worlds. The power to transform remains solely in the hands of celestial powers: creation, even artistic creation, is the prerogative of the Creator.

Thus Symphonia does not change the world, but expresses it. It is an extension of what there is, the active mark of the involvement of the nuns of Bingen in the beauty of the universe. The work has no vocation other than to do justice, in other words to be beautiful as soon as it is produced. It is the exact opposite of distraction: not cutting listeners off from reality, but rather making them closely involved in the harmonious order of things.

His incredible music ignores artificially curtailed temporalities. It does not follow the linear time of incident and progress, but a circular one of memory of self-abnegation. Its tempo matches human thought, a heartbeat, the present mood or a fire’s heat. Its melodic progressions imitate natural harmonies, follow the trajectory of sounds emitted beneath Roman vaults that produce an effect of comforting concordance. Placed end to end, the dozens of pieces that make up Symphonia merge into a unique and crackling undulation – it is a flame, a heart, an exercise of a pure present.

There are dawns, middays and dusks, clear winters and long summer evenings, echoes from mountains and heavenly lullabies. The strings of the bandura played by Marie-Pierre Brébant shine. This Ukrainian instrument, a mixture of a lute and a harp, is tuned to the Pythagorean temperament. Without doubt created in Turkey, modelled by the Italians and adopted by the Cossacks, there was little to suggest that it would be destined to encounter Hildegarde’s music. Yet it becomes an ally of it, inventing a new voice for these scores. A harp of David and an angelic lyre in one, it combines Edenic gentleness and the tension of metal strings: heaven and earth.

Strong shadows define François Chaignaud’s muscles. You see the breath fill him, tensing him, coming out again and reappearing, singing can be seen suddenly emerging from his flesh. The monody is a narrow passage, a humble trajectory that the harmony needs for its duration in order to unfold. It shows a unique place, places itself at a precise point and concentrates. As old as the score is, it is an exercise of the present, a way of taking shape with the moment. […]

On stage the cosmos is the neume: a bridge, a Roman platform that the artists cross, inhabit and circumvent. It is the theatre of existence, with its exaltations and angers, its hopes and dramas, the scene of everything that was, is and will be. The audience is invited to sit or lie around, to listen and watch, to dream, ponder, sense and feel, to sleep and observe, to be delighted, moved and shifted. They can choose to get up and lie down somewhere else, move from one side to the other. Coming face to face with Symphonia involves finding a place in a harmony that goes well beyond us.

Léo Henry

•••

Léo Henry (b. 1979, Strasbourg) is a French author and scriptwriter. After his master’s degree in modern literature, Léo Henry travelled to the United States and lived in Brazil. In the late 2000s, he began working with Jacques Mucchielli (who died in 2011), with whom he published four books. Modernity and popular music are among his favourite subjects. In April 2018 Léo Henry published the book Hildegarde, a biographical novel about the figure of the German nun, composer, poet and botanist Hildegard of Bingen, which he now considers to be his masterpiece (published by La Volte).

Conception and performance: François Chaignaud and Marie-Pierre Brébant

Based on the musical work of Hildegard von Bingen (1098–1179)

Musical adaptation: Marie-Pierre Brébant

Scenography: Arthur Hoffner

Light creation: Philippe Gladieux, Anthony Merlaud

Sound design and sound-space setting: Christophe Hauser

Artistic collaboration: Sarah Chaumette

Costumes: Cédrick Debeuf, Loïs Heckendorn

Tattoos: Loïs Heckendorn (creation), Micka Arasco (print)

Stage manager: Anthony Merlaud / François Boulet

Latin prosody: Angela Cossu

Administration and production: Barbara Coffy-Yarsel, Chloé Schmidt, Jeanne Lefèvre, Clémentine Rougier

Distribution: Sarah de Ganck / ART HAPPENS

Production: Vlovajob Pru – Vlovajob Pru is subventionned by Ministery of Culture (DRAC Auvergne Rhône-Alpes) and Conseil Régional d’Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes. François Chaignaud and Cecilia Bengolea are associated artists at Bonlieu Scène nationale d'Annecy.

Coproduction: Kunstenfestivaldesarts ; Bonlieu Scène nationale (France) ; PACT Zollverein (Germany) ; Centre chorégraphique national de Caen en Normandie – direction Alban RICHARD dans le cadre de "l'Accueil-Studio" (France); Ministère de la Culture et de la communication (France) ; BIT Teatergarasjen Bergen (Norway) ; Arsenal/Cité musicale Metz (France) ; CN D Centre national de la danse (France) ; MC93 Maison de la Culture Seine-Saint-Denis, Bobigny (France) ; Les 2 Scènes, Scène nationale de Besançon (France) ; La Bâtie, Festival de Genève (Switzerland) ; TANDEM Scène nationale (France) ; Festival Musica Strasbourg (France)

With the support of: Villa Noailles, Hyères (France) ; CN D Centre national de la danse (residency) ; BoCA (Biennale of Contemporary Art) Porto (Portugal ; La Métive international venue for artistic creation (residency) ; Moutier d’Ahun – FRAC Franche-Comté, Besançon (residency); Les Subsistances, Lyon; French Institute and the Fench Embassy in Belgium, in the frame of Extra

Thanks to: Lucie Jolivet, Lyubomyr Shevchuk, Catherine Schroeder, Léo Henry, Eugénie de Mey