07 — 25.05.2013

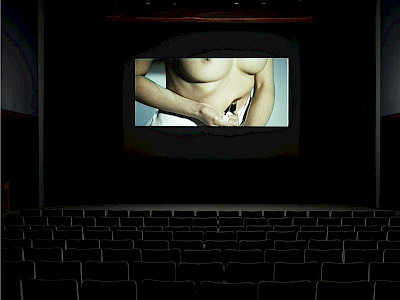

While being acclaimed recently for his stage performances, Markus Öhrn primarily works as a video maker in the field of visual art. His installation Magic Bullet is a chronological montage of all the film scenes that were cut by the Swedish censors between 1934 and 2002. Sixty-eight years of cinema showing an evolution of forms, but above all an evolution in sensibilities as well. Because what was deemed unacceptable yesterday will not necessarily be so tomorrow; it is perhaps the revelation of what it wants to hide that says the most about a society. By removing from invisibility a series of images cut at specific times in history, this conceptual 49-hour-long work poses the question of censorship today. While state censorship has largely disappeared from our liberal cultures, it has been replaced by an internalisation of social control that is doubtless more insidious. Power struggles continue to hide behind the “end of censorship” …

Swedish artist Markus Öhrn created the 49-hour-and-13-minute-long film Magic Bullet from every censored film clip preserved in the Swedish state film archive in Stockholm. This censorship bureau was the first of its kind in the world, and was created in 1911 to defend the population against the medium of film, which was considered to be a 'magic bullet' that could penetrate the brain and infect the thoughts and actions of the masses. By showing a film comprised of every censored cut in chronological order, Öhrn holds up a mirror to Swedish society's shifting and contradictory moral worldview. At the same time, he seeks to understand how censorship works today, as Swedish film censorship ended in 2011, precisely one hundred years after its creation.

What initially inspired you to make Magic Bullet?

In 2008 I was at the national library in Stockholm doing research for a video installation. This is where they have all the archived films from Swedish television and so on. I was exploring how the anus is a suppressed erogenous zone in our culture, and in the listings I came across an instruction film on anal sex. When I requested the film, they said that it is a censored clip that was cut out of a documentary in 1974. I asked if there was an archive of censored film clips, and they informed me that indeed there was, the Swedish Bureau of Film Censorship, where every cut is archived and regarded as a public document. My thought was that if these censored film clips are regarded as part of the public domain, then I must have the right to copy the whole archive. If I could make one movie out of all these censored film clips, and just put them in chronological order, this movie would, in a way, mirror Swedish social norms. Like in psychoanalysis, it's what you leave out that indicates what you really want to show. It becomes a mirror of society. So if they cut out all the gay scenes in a movie - in the 1960s, for example, they did a lot of that - then you know that the Swedish government didn't want its inhabitants being inspired to 'become' gay. This is a good example of how the Swedish government wanted to control people's sexuality.

Why is the film called Magic Bullet?

When public film screenings began in Sweden in 1896, the fear of their negative impact on people was widespread. Film was thought to be a medium with the power to control the viewer's mind. Behind this perception was the so-called Magic Bullet theory, which compared film to a magic bullet that penetrates the brain and takes control of one's thoughts and actions. This was at a time when a lot of people were moving from the rural regions into the big towns, and film screenings were amongst the first cultural exchanges they made. So the state was afraid that the things that happened in a film would unduly influence this uneducated mass of people. When in 1911 the Swedish government decided that every film had to be censored, they decided to create the first state censorship bureau in the world.

Does the fear that film can control our actions remain?

No, today that fear has moved to newer media like violent videogames, which we try to blame for school shootings, etcetera. But human beings have always carried an existential fear of some external influence taking harmful control of the mind. Plato had said that we should be careful what stories we tell to children. We all know the existential fear of taking drugs, that you wouldn't be able to control your actions, that you would maybe kill someone or something.

Why did you decide to use every piece of censored material and thereby create a very long chronological film?

As soon as I gained access to this archive to see the censored clips, I looked through a surrealistic mix of everything from violence to dialogues about homosexuality. I immediately decided I didn't want to select the clips but instead to digitise the whole archive, to copy everything chronologically, because it creates a story about Swedish society that is exceptional. It's a backwards way of looking at the social norms. I felt the whole idea of the project would collapse if I started to censor the censored material. We have to remember that this archive is unique. Usually an archive is an act of censorship because we determine what to retain for the future. I wanted to stay true to this archive - which is, ironically, uncensored - by not censoring it. But what I'm ultimately doing in Magic Bullet is taking everything that has been regarded as violent or sexual or dangerous, and creating a new value.

Why was the Swedish film censorship bureau shut down in 2011? Does this mean that censorship is now over?

After 1996, the censor didn't cut films anymore because it became a blunt weapon, since anyone can access this content via the internet or videos or whatever. From then onwards, they merely classified films. In one way, censorship was over. But just because state censorship has finished in Sweden doesn't mean that censorship is gone. It has just moved somewhere else. So my intention for this project is to provoke that idea, that discussion. Where is the censorship today, where has it moved? Because we know it's not gone. It's just shifted from state control to corporate control. Economic interests and branding are the censoring organs today, not the state. And that usually means more censorship. The problem is that we will never know what is cut out of movies today. The production companies that impose censorship control definitely don't keep an archive that any citizen or researcher can access.

Is the internet even censoring itself?

Yes. YouTube is the perfect example. They don't censor anything themselves; it's only if you, the user, find it disturbing and you yourself flag it, that they will look at it. But then, without any explanation, they will either let it stay or remove it. So no archive is kept, and they don't need to give a reason if they decide to take away content that users find disturbing. The users themselves drive it and this is the new landscape of censorship, which is actually much more severe. I mean, if you now show naked breasts or make a joke about religion, it's really hard to say whether YouTube or Facebook will delete the content. We just accept that they will clean it up. This is the biggest problem. So we don't post naked pictures of ourselves on Facebook because of knowing they will disappear. There are other things too. Apple, for example, doesn't accept any apps that have anything to do with pornography. They totally censor their interface on iPads and iPhones. Any app that you download to Apple is previewed to ensure it conforms to the company's values. There was an app that gave updates of US drone strikes, but Apple denied it. This is, in a sense, a proxy act of censorship for the American state. Apple is a powerful gatekeeper that can stop criticism of its own company and of government policy. So whether it's film or internet content, our society is more censored today than ever before, even if official state censorship is gone.

Since creating Magic Bullet, have you watched the whole film from beginning to end?

Yes, but not in one go.

Were you disturbed?

No, I felt I had learnt something.

A film by

Markus Öhrn

Thanks to

Tobias Jansson, Jan Alvermark, Marius Dybwad Brandrud, Skogen Produktion, Magnus Liistamo, Statens Biografbyrå, National Library of Sweden

Presentation

Kunstenfestivaldesarts, Beursschouwburg

Supported by

KU Nämnden Konstfack (Stockholm), Swedish Arts Grants Committee