04 — 06.05.2012

In addition to reconceiving the codes of ballet, William Forsythe has challenged the norms of theatre by creating installation-performances that combine movement, words and technology. He returns to Brussels with a masterly new dance work in which his hyperkinetic language is replaced by more organic movement. Inspired by the rhythmical inflections of the Elizabethan stage, Sider presents a group of dancers – neither “insiders” nor “outsiders,” or maybe both at the same time – who, equipped with earphones, respond to a score unheard by the audience. As they move with cardboard panels, they (de)construct spaces of ambiguous meaning: perhaps temporary shelters, perhaps protective walls. On one board the phrase “is and isn’t” offers potential reference to Hamlet’s monologue but at the very least indicates an existence confronted by its own destruction. Encompassing a world of possibilities, Sider allows the frailty of human action to rise to the surface.

« De 1984 à aujourd’hui, William Forsythe écrit comme à l’envers, se réinventant jeune chorégraphe avec la complicité de ce que l’on peut nommer une «troupe». »

Marie-Christine Vernay, Libération

unpredictably unpredictable

Choreographed by William Forsythe, the Forsythe Company’s recent Sider is something of a complex puzzle, a riddle you just cannot solve. And yet the stage setting is extremely simple: it has been reduced to four small trusses fitted with neon lights flickering on and off at irregular intervals and with changing light intensity. Created by Spencer Finch, this light object is reminiscent of Three Atmospheric Studies (2005), although it conjures a very different atmosphere. ‘The variations in colour and intensity are based on English and Danish skies’, says Forsythe. Besides that, only a few sheets of simple corrugated cardboard make up the set. These sheets are slightly above life-size, so that someone can hide behind them or be buried beneath them. There are only three at first, laid out randomly on stage. At the show’s end, however, there are close to twenty scattered across the stage, while the dancers disappear one at a time.

The riddle, in any case, is not contained in the cardboard sheets, even though two of them bear an inscription. A sheet shown at the start reads ‘In disarray’, while another appears at the end with the inscription ‘Is and isn’t’. Clear enough: one starts out from a state of disarray. The performance will make these sheets mean something or represent something, but in the end they revert to what they were in the first place, nothing more than a heap of cardboard sheets. They are, and they are not. The sheets thus clearly indicate that we are watching an imaginary performance in which anything can stand for anything, merely through the intentionality of the actions performed by the dancers.

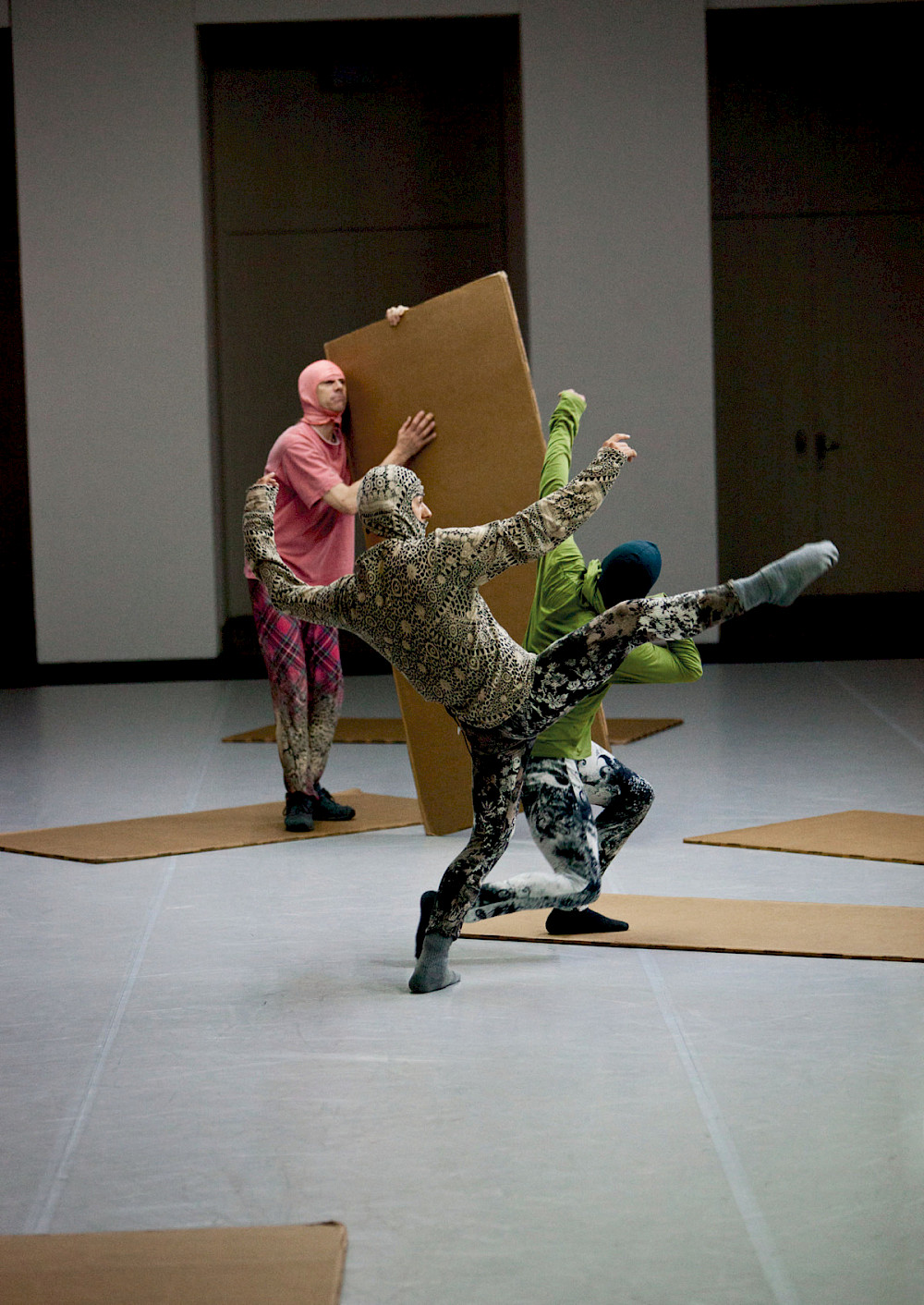

It is in these actions, however, that the show’s delightful riddle rests. The dancers introduce an overwhelming amount of information. Even though there are only three dancers on stage at the start, a lot of attention is required to take in everything that is happening, and therein lays a major paradox. Fabrice Mazliah, Roberta Mosca and David Kern, the pivotal figures around which the play is built, all move with such precision and detail that one immediately supposes that there is a specific purpose to their performance. Mosca juggles with two sheets, which she assembles in all possible configurations or lets lie on the floor while she staggers unsteadily back and forth and up and down. Mazliah stands close to her, and at times slips between Mosca’s fast changing constructions. At other times he keeps more of a distance. His twisting and wriggling make him look like an explorer in a narrow cave. What do these two have in common, besides their proximity? Since no answer is immediately apparent, one keeps searching for new details that can lift a corner of the veil. Is there a story behind this, or is it an abstract composition? What principle governs the timing, the distances, the use of sheets? The only constant seems to be Thom Willems’s score: a heavy humming tone that swells up and fades away, before growing later into a deafening roar, creating a true Doppler effect or else outlining the bare bones of a melody.

These details proliferate further when more and more dancers in extravagant costumes created by Dorothée Merg make their appearance. Many of them wear balaclavas, while their pants and tops feature all sorts of strange prints. Here and there one notices a historical detail, such as a lace collar typical of the 16th century. It is as if all sorts of elements had been assembled to create a historic scene in a fanciful manner – without striving for accuracy, however. In this, too, the performance remains a play with signs.

But then there is the language. After the first scene one catches a man talking in the dark, uttering incomprehensible gibberish. In colour, sound variation and intonation, it unmistakably recalls the artificial, self-conscious expressivity of English theatre we are familiar with from representations of Shakespeare, say. Even though one doesn’t understand a word of what’s being said, one suddenly realises that somehow or other, a play is here being performed. Or, more accurately, that the action one is watching is analogous to a play. All the ingredients are there: a set, dialogue, costumes, movement, sound and light. And these elements fit into one another so precisely that it is only possible that a primary meaning underlies them. Yet that primary meaning resists being named.

That is because that primary meaning is not so much a story as a formal pattern, namely that of Elizabethan theatre. Forsythe was indeed fascinated by the structure and musicality of Elizabethan language. ‘It was an amazing historical era. There emerged during that time a very complex and florid language which ties in with equally complex conceptions of the use of space and time. The structure of the language forces you to speak a certain way, with specific inflections, and at a specific rhythm. The art of using the language in such a way was passed on from one generation to the next, in roughly the same way as the manner in which ballet techniques have been passed on to us’. For the dancers at least, this form of theatre is also very much present, since the text of a piece from that era is continuously fed to them through a small earphone while they dance. This colours what they do, without fully determining the action. As a spectator one doesn’t really know this, however, and one can only guess so.

The dancers’ movements also follow another logic, however, as Forsythe explains: ‘I had started out from the idea that something is inevitable. The French have a beautiful name for it, the “futur antérieur”: “it will have happened”, the inevitable course things will take. You can also apply that idea to a play that will be created in the future. So we interviewed the dancers about that show that thus didn’t yet exist. During those interviews, like a kind of “language pus”, non-existent words emerged such as “flabimpunist”. We arrived at a list of about 80 words in a non-existent language, although it is related to English’.

‘Another strategy consisted of asking the dancers to draw a map on a transparency, which was then projected onto the space as a 3D model. Just as in Alie/na(c)tion we connected words with specific points in space. The dancers thus often follow their own private map to find their way. Their interpretation of it does not necessarily coincide with that of the others, and sometimes not at all. For instance, Roberta Mosca moves at the start through an imaginary Sumerian village. She conjures it with two cardboard sheets, as if she were building a cardboard castle. Fabrice Mazliah moves between the sheets, but in his view they don’t represent a Sumerian village at all. And so that’s how tension is added to the set. It is very difficult to choreograph. That’s why I often intervene through the earphone they wear during the performance’.

One immediately understands why the performance is so complex and so enigmatic. At least three rhythms cross one another: the ostinato sounds created by Thom Willems, the lighting variations, and the rhythm of the text that also defines the rhythm of the movements. Besides that there are the dancers’ various ‘cards’, which sometimes coincide with the text they hear. That is precisely what defines the work’s appeal. Forsythe: ‘We work here with very powerful formal systems, but I continually shatter their logic by inserting exceptions. But before they notice that, I also shatter that logic by inserting exceptions to that exception. It all has to do with how the human brain works: it’s always looking for patterns and connections so as to be able to predict the unfolding of an event. Once that becomes clear, however, a spectator’s attention weakens. That’s why I keep pricking it over and over again’.

The spectator is indeed an important player and contributes to the completion of the performance. The performance underlines this aspect by means of short text messages that light up now and then: ‘She is to them as they are to us’, or ‘They are to us as we are to them’, phrases that underline the extent to which performers and spectators depend on one another.

These explanations can help one understand how the play functions in principle. That it also works in practice, however, is a miracle of performance skills and pleasure. One watches as the performers continuously throw themselves into situations in the craziest possible manner before getting themselves out of it, build things up and develop them before letting them deteriorate, or beat out complex rhythms on the cardboard sheets before letting them die out. And one observes how, in the end, after all the commotion, things fall back into place when the opening scene returns in a slightly altered form. A tour de force.

And by the way: the title of the play derives from ‘side’, as in ‘the side of a sheet of corrugated cardboard’, the raw material with which the performers go to work.

Pieter T’Jonck

(translated by Patrick Lennon & David Camacho)

A work by

William Forsythe & The Forsythe Company

Music

Thom Willems

Light object

Spencer Finch

Lighting

Ulf Naumann, Tanja Rühl

Sound design

Dietrich Krüger, Jennifer Weeger

Costumes

Dorothee Merg

Dramaturgical & production assistance

Billy Bultheel, Freya Vass-Rhee, Elizabeth Waterhouse

With

Yoko Ando, Cyril Baldy, Esther Balfe, Dana Caspersen, Katja Cheraneva, Brigel Gjoka, Amancio Gonzalez, Josh Johnson, David Kern, Fabrice Mazliah, Roberta Mosca, Jone San Martin, Yasutake Shimaji, Riley Watts, Ander Zabala

Presentation

Kunstenfestivaldesarts, Théâtre National de la Communauté française

Production

The Forsythe Company (Frankfurt/Dresden)

The Forsythe Company is supported by

the city of Dresden and the state of Saxony as well as the city of Frankfurt am Main and the state of Hesse. The Forsythe Company is Company-in-Residence of both HELLERAU – European Center for the Arts in Dresden and the Bockenheimer Depot in Frankfurt am Main.

With special thanks to

Ms. Susanne Klatten for supporting The Forsythe Company

Supported by

Goethe-Institut Brüssel