22 — 26.05.2012

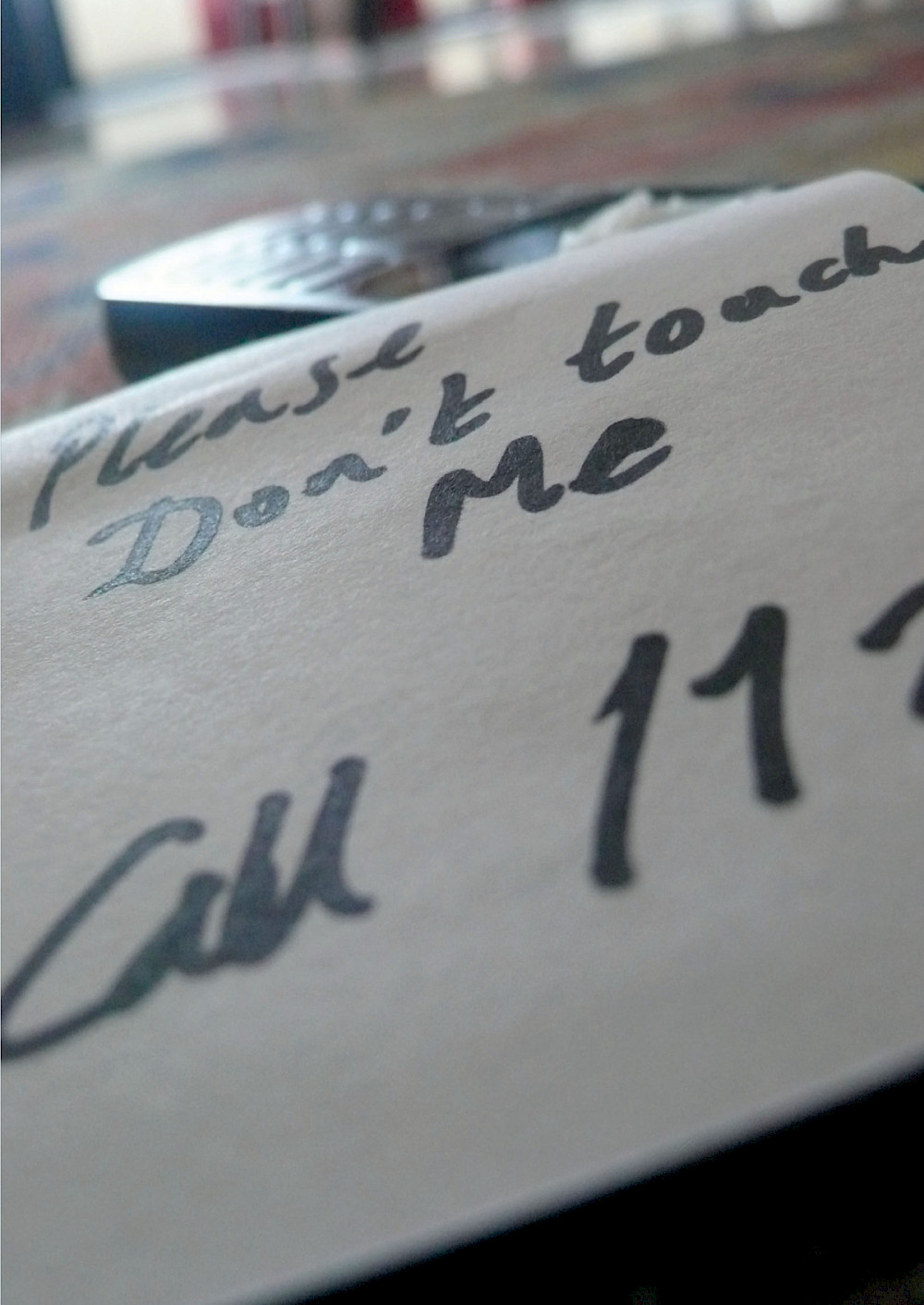

A young Lebanese man ends his life. In his farewell letter, he asserts that his death is a personal act and cannot to be used for political purposes. Rabih Mroué and Lina Saneh, who work as writers, directors and actors in Beirut but are known around the globe, invite us to follow the final days of this imaginary character, as well as the reactions to his suicide. They reconstruct his bedroom where everything continues to live, vibrate and communicate: his television, answerphone, Facebook page, printer etc. This world no longer has any need of a human presence to operate or to create history; information continues to pour out unperturbed… In this semi-documentary show being premiered at the festival, the artistic pair ponder the political paralysis in Lebanon, a country where no spark seems to have been lit by the fire of the Arab revolution. What does this inability to react mean? Can an act of despair like this revive any hope of change in such a divided nation?

33 tours et quelques secondes

Rabih Mroué & Lina Saneh

“For each new performance, Lina and I start with the same simple question: What themes are we on about? This time it was the politics in Lebanon, but in light of everything that was happening in the Middle East, we suddenly felt there was no longer the same urgency towards it. The Arab Spring kept us very busy. Only what was really to tell? And how?”

Rabih Mroué is not one to simply copy reality as it occurs. Yet that is exactly what many Arab artists today feel compelled to do. They express themselves over the Arab Spring in documentary form. They film, draw, record and play what happens in the street. Along with the protesters, they lay down a huge archive of testimonies.

Rabih Mroué and Lina Saneh, an artist couple from Beirut, have more or less always taken a documentary approach, ever since their first performances and videos in the 1990s. They just fish typical facts or anecdotes out of their own lives or out of Lebanese history, which help explore a much wider question. In Looking for a missing employee Mroué used a series of newspaper articles about a disappearance in order to reflect on the public space in a divided country. In Appendice Saneh made a narrative account of her very own opposition to the ban on cremation in Lebanon: she auctioned her body parts.

In each case, it concerned performances that necessitated an insight, a critical distance that these underlying structures can discern in the swirl of everyday life. “In order to consider something, you need distance”, confirms Mroué. “But how do you measure that distance? There are no rules for this. Maybe you would need one day for it, and I would need a hundred. Some artists have succeeded to reflect on the revolution in a fascinating way while it is still in full swing. But there are also certain Lebanese artists who after twenty or thirty years still find nothing interesting to say about the civil war in Lebanon, because they are too entrenched in it. How do you then create that distance in the face of a very complex topicality? That is not obvious.”

Still, you have chosen to depart from your sense of urgency concerning the Arab Spring. What tipped the scales?

“I believe in the accumulation of your experiences through time, of your ability to ask questions. That also helps you approach a topic differently. We are not obliged to create a performance about the Arab Spring if we have nothing to say about it. I believe in procrastination, I am against hasty artworks. But if you think that you have a good question, which is ready to be shared, why should you then not go for it?”

What has come out of it? What do we see?

“We have kept it close to our hearts, to what we know. In 33 tours et quelques secondes the Arab Spring only forms the background, while in the foreground it is about socio-political issues in Lebanon itself. The situation is that a young man has committed suicide. You see the after-effects of his death. What do his friends think? What does Lebanese society think? There are no actors. The scene depicts his room, where reactions enter via all kinds of communication devices: on TV, on his Facebook page, by text message, and also on his landline. The room stays alive, it reacts and comments. This ultimately provides a reflection on how Lebanon deals with the Arab Spring, on the inability to take decisive steps.”

Do you recognize that as being a global problem, or just something typically Lebanese?

“We present a very local Lebanese story, but it will still evoke many associations with other stories in the world. Or at least we hope so. Lina and I are never concerned with who our audience is, otherwise it leads to compromising in order to consciously please or provoke. Our work is always unfinished; it must continue beyond the actual performance. You share your thoughts with many different individuals throughout the world and hope that it produces debate, but you can never anticipate what will turn out. “

Which thoughts do you consciously work into the performance?

“One layer is the political background in Lebanon. The country is trapped in its confessional system, like in a mousetrap. Why is our generation unable to cope with what is happening? Normally, because it is such a fragile and unprotected country, Lebanon is immediately ignited by what happens around it. You now get the feeling that the Arab Spring provides a lot of tension, but everyone silently abides. Once there were a few demonstrations, but because there are many powers in Lebanon and not one dictatorial authority against which to protest, that resistance was doomed to failure. Even politicians dare not take steps or make statements. Especially with regard to Syria, with which Lebanon shares a heavy history. What is now going on there is very sensitive. The Lebanese people dare not accredit it. It is deeply divided over Syria. The one camp sees a revolution, the other a conspiracy against the government. But Syria remains a huge taboo.”

In that light, what is the function of all the means of communication that are so central in the performance?

“They obviously do not have one function. Facebook, television, mobile, telephone: these are very different media. I was not even on Facebook earlier, but since the Arab Spring I was. I make no value judgment on it, but you cannot ignore the phenomenon itself. In Lebanon and in the whole of the Arab world, we are lacking a public space. If it already exists, it is very limited in time and scope. Whether Facebook fills that gap is difficult to generalize. In Syria, Egypt and Tunisia, Facebook has always been used differently than here. The Iranians used Twitter during the Green Revolution. It is therefore interesting to see how these tools change depending on the context. What do they promise? Where do they fail? We were especially interested in the use of these new media within such an old medium as theatre. That was a real fight, especially aesthetically. We only have a stage set, no actors. How can you create the here-and-now with mere machines? It’s like dancing without dancers. What it becomes, we’ll see. What fascinates us is not the result, but the question. It leads to new insights in our dealings with theatre.”

How do you look at the overall role of artists in situations such as the Arab Spring?

“That role is no different than in Iceland or Belgium. We believe that art may not become activism, because then you serve ideological ideas. No, art is a portrait of your own taboos and key questions. You have to challenge yourself, betray your own beliefs. Sometimes that feels violent, but there is no alternative. If I already know the answer, I cannot begin on a performance. Then you are going to manipulate the whole in function of your underlying message. Then you no longer address your audience as individuals, in order to divide them into for and against. And that’s essential. If you address people as a mass, you are like the teacher who wants to impose knowledge. Of course, as an artist, you do have a certain authority and responsibility. I see theatre as an empty space that fills you up for a short time, only to then disappear again as soon as possible. You may not occupy it, you’re there as a guest. That is precisely what makes theatre a public space: later someone else can also come.”

And retrospectively? Can you look back on your work and discern certain common threads?

“There are definitely certain characteristics that come back, but I’m not necessarily happy about that. You would want to deconstruct your own style again and again, only that proves difficult in practice. In some sense, our work is classic: there is always a story, a plot. But we approach it otherwise. If I were not so averse to labels, you would be able to speak of a postmodern approach. Thus, a clearly common thread is that we always indicate the mechanisms of the performance in the performance itself, so there’s a certain Brechtian inspiration. By revealing your tricks, you make people conscious of your manipulation. We find that important.”

Wouter Hillaert

Translated by Jodie Hruby

Text & direction

Lina Saneh et Rabih Mroué

Graphic design, animation & scenography

Samar Maakaroun

Technical assistance

Sarmad Louis, Thomas Köppel

Translation

Ziad Nawfal

Director of photography

Sarmad Louis

Assistant

Ahmad Hafez

Casting & executive production

Petra Serhal

Editing

Najib Zeitouni

Actors

Nagham Abboud, Samir Abou Jaoudé, Thomas Bowles, Edy Gemaa, Raseel Hadjian, Colette Hajj, Wadad Hneine, Paul Khodr, Ibtisam Kishly, Eliane Mallat, Muriel Moukawem, Elie Njeim, Antoine Ozon, Najeeb Zeytouni

Voices

Rabih Mroué, Lina Saneh and others

Thanks to

Famille Baroud, Janine Baroud, famille Mroué, Kinda Hassan, Paul Khodr, Raceel Hadjian, Sari Louis, Paul Matar, Abdo Nawwar, Walid Raad, Christine Tohmé, Yelda Younes, Theatre Tournesol and others

Presentation

Kunstenfestivaldesarts, Beursschouwburg

Production

Kunstenfestivaldesarts

Co-production

Festival d’Avignon, Scène nationale de Petit-Quevilly – Mont-Saint-Aignan, Festival delle Colline Torinesi (Torino), La Bâtie – Festival de Genève, Kampnagel (Hamburg), Association Libanaise pour les Arts Plastiques, Ashkal Alwan (Beyrouth), steirischer herbst (Graz), Malta Festival (Poznań), Stage – Helsinki Theatre Festival, Théâtre de l’Agora, Scène Nationale d’Evry et de l’Essonne

Thanks to

Éditions Jacques Brel