19 — 23.05.2009

The founder of the Socìetas Raffaello Sanzio says he wants to create a theatre that doesn’t convey a message but which has a direct impact on the spectator. “I look for the key themes in obscure materials, and I manipulate emotions through images which communicate themselves in a still movement in space-time.” Nothing could better illustrate the truth of these words than this trilogy, a work of implacable violence and absolute aesthetic force. Its third and last part, Paradiso, is a vision that the spectator enters alone for a few minutes. A black hole where the only possible light is to be found within oneself. For Castellucci, “Paradise” is the most dreadful part of the Divine Comedy, “a form of inverted exclusion”. A space for silent contemplation, in which humanity dissolves and from which all subjectivity has been excluded. First and foremost, that of the artist...

An illustration of the disaster

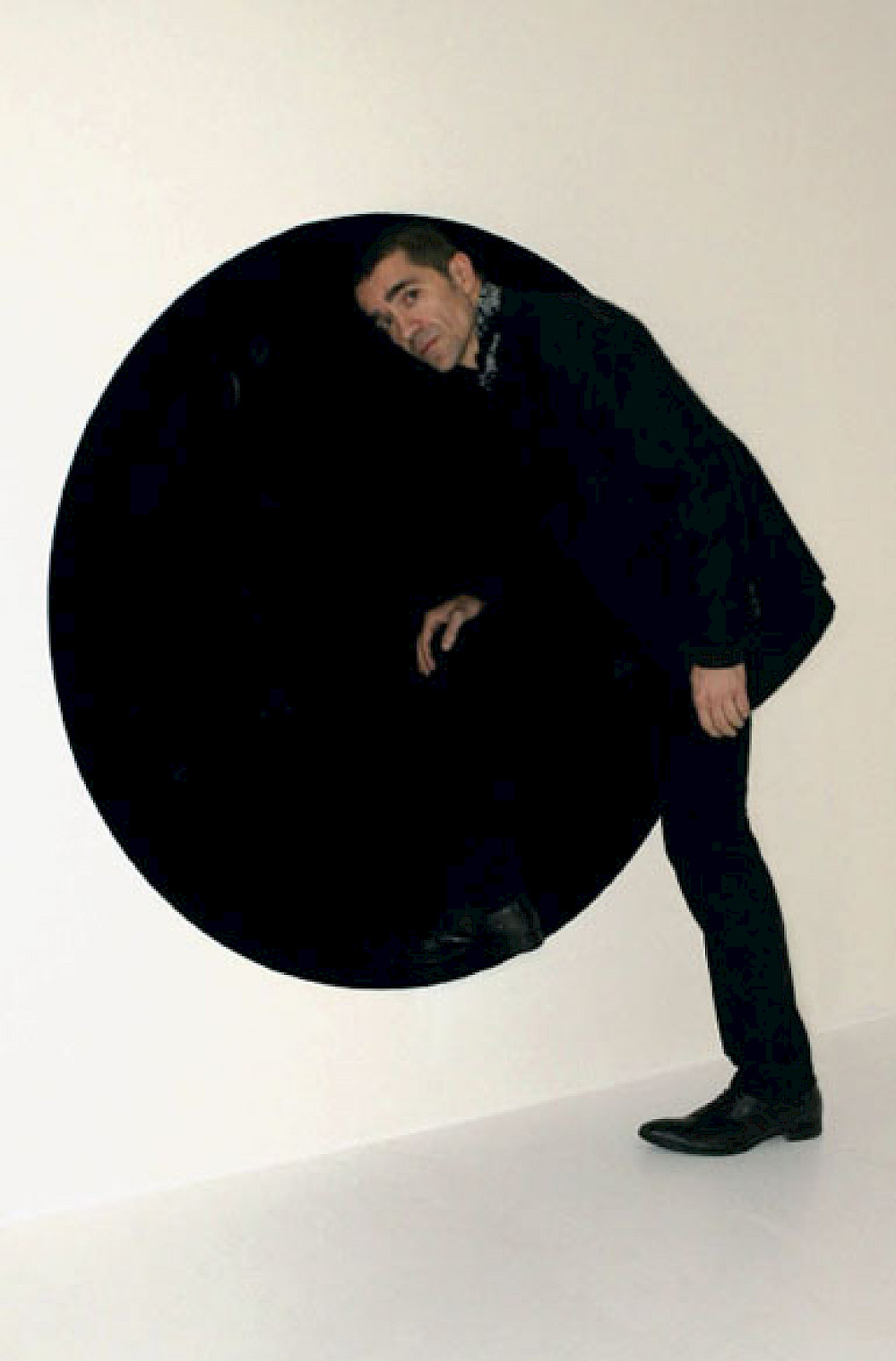

The church of Santo Spirito in Cesena is invaded by a huge cube which almost fills the entire central space of the building. The spectator is introduced into a room of dazzling whiteness. It's a decompression chamber. A round opening, like a huge eye, looms out of the middle of the one of the walls. This black rosette, like a bottomless shaft, reveals itself to be a passageway. Perfectly in keeping with the final image of Purgatory, this dark centre leads to a completely black room, in a space without reference points where darkness reigns and the senses are challenged. You can hear the deafening sounds of flowing water as you literally feel your way in the dark. Your eye is suddenly drawn to something that appears to be a barely perceptible point of light, tiny, something you feel you're being watched through, caught in a trap. Meanwhile the water continues to flow and forms a dimly shining pool where, in a faint and sinister reflection, you notice a presence above. A human one? Like a diabolical image, the silhouette freeing itself little by little literally seems to be buried in the wall to its waist, emitting brief moaning sounds, as if in regret.

The person seeing - the spectator who is no longer outside of what he sees - is led towards a place the human eye cannot reach and experiments with a kind of blindness, heightening his other senses in the darkness.

In the realm of bright light, doesn't Dante have recourse to the upward climax of light to the point where the blessed completely dematerialise? Doesn't he gradually reach the flying souls' "convent of white stoles" and, in the end, the Empyrean? Hasn't Dante linked the situation of radical light saturation, to which the spectator's eye is subjected, to a definitive ban on vision and language? Doesn't the story end when the witness's memory fails? Doesn't it produce in God a paralysis in the act of seeing?

Romeo Castellucci's Paradise is on the side of catastrophe, at the very point where vision creates a crisis in language before the immeasurable vision of God. But the paradisiacal part is not between the visible and the invisible. The sensory disjunction at play in moving from a space of whiteness to a space of darkness is not just provoked by experiencing the limits of our visual faculties, but by a growing feeling of solitude. Both part of the same tableau, the two spaces which constitute the brief paradisiacal journey outline a topological object where it is impossible to distinguish the external from the internal: there is a hint of the artifice of eternity as a place where various solitudes combine. The effort of the glimpsed silhouette and the optical effort of the spectator generate a kind of timeless agony: a desire for the end, stuck in an image that has no alternative but to last. In the absence of any kind of apotheosis, the tension between the two spaces does indeed seem like a state of conflicting equilibrium: the amnesiac void, the rejection of any narrative development, a before and after incapable of rebirth or destruction.

So the central element of Paradise is precisely this almost imperceptible silhouette, a sting, a stain, a tiny slit in the field of vision or, as Lacan put it, the barred subject falling within the frame of vision. Like an assertion that has lost the thread of the discourse, Paradise settles precisely over this already/still missing and elusive "hole" to make way for the unrepresentable.

*Piersandra Di Matteo

*Piersandra Di Matteo is an art critic and theatre historian. She is conducting research at the DMS/University of Bologna, mainly concerned with contemporary productions, and contributes to a number of journals specialising in this area.

La Divina Commedia

by Antoine de Baecque

The Divine Comedy is a sacred poem by the Florentine poet Dante Alighieri (1265-1321) and comprises three parts - Inferno (Hell), Purgatorio (Purgatory) and Paradiso (Paradise) - each with thirty-three cantos plus an additional introductory canto. Written between 1307 and 1319 towards the end of his life, it was with a sense of relief and some melancholy that Dante completed this work of one hundred cantos and close to 15,000 lines. The Divine Comedy was composed at the time the papacy came to Avignon and the first Palais des Papes was built. For western culture, it is more than just a literary monument; it is a work of reference. Even for those who have never read it, the work makes sense. It is like a mythical country - we visit its underworld and fear its troubles, we travel through paradise and hope for its delights. Its images, visions and hallucinations and the range of registers (including love, mysticism, learning, allegory, politics and poetry) have also been a source of fascination for numerous writers and artists: many of them - Dumas, Stendhal, Baudelaire, Nerval and Lautréamont to name but a few - have translated it to appreciate its richness fully. Romeo Castellucci is now seeking to "transpose The Divine Comedy to the stage", offering audiences an opportunity to work their way through its three stages at three different Festival venues and experience a Divine Comedy.

Direction, set design, lighting & costumes

Romeo Castellucci

With the participation of

Dario Boldrini, Michelangelo Miccolis, Davide Savorani, Martin Deweez

Collaboration to the set design

Giacomo Strada

Sculptures on stage, mechanisms and prosthesis

Istvan Zimmermann and Giovanna Amoroso

Presentation

Les Brigittines, De Munt / La Monnaie, Kunstenfestivaldesarts

Production

Socìetas Raffaello Sanzio

Coproduction

Festival d’Avignon, Le Maillon-Théâtre de Strasbourg, Théâtre Auditorium de Poitiers–Scène Nationale, Opéra de Dijon, barbicanbite09 London, deSingel (Antwerp), De Munt/La Monnaie (Brussels); Athens Festival; UCLA Live (Los Angeles), La Bâtie (Genève), Emilia Romagna Teatro Fondazione (Modena), Nam June Paik Art Center/Gyeonggi-do, Korea, Vilnius – European Capital of Culture 09, Vilnius International Theatre Festival Sirenos, Cankarjev dom / Ljubljana, F/T 09 Tokyo International Arts Festival, Kunstenfestivaldesarts