14.05, 16 — 18.05.2002

It was pure chance that led Khoury and Mroué to come across the filmed testimony of a suicide fighter, Jamal Sati, in 1999. In it the ‘martyr’-to-be says his goodbyes to the Lebanese people. With each passing frame, the words, tone, manner and even the contents change. Khoury and Mroué still had questions they wanted to ask after seeing it, and a desire to make a production based on it. Three posters, made in 2000, lends a voice to the ‘martyrs’ of the Lebanon’s most forgotten history: that of the 1975-1990 civil war that tore the country apart. More than anything, however, it provides food for thought about the information we receive and how it is manipulated. Since 11 September 2001, the mix of true and fictional testimonies – the actor’s, the suicide “resistance fighter’s” and the communist politician’s – convey a number of questions that have taken on new dimensions.

1984.

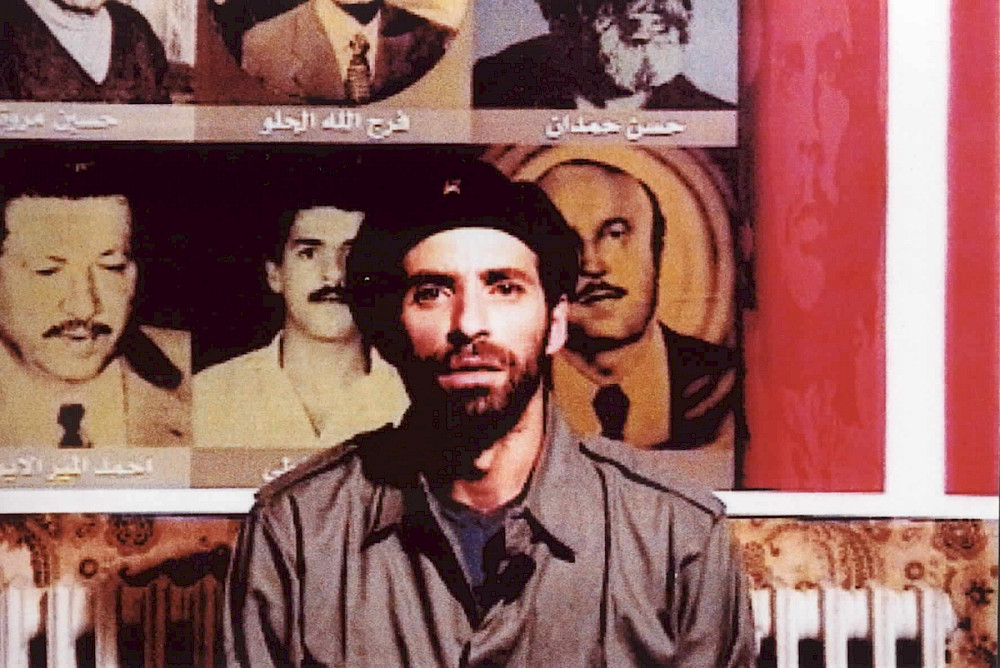

In 1984 a member of the Lebanese Communist Party, Jamal Sati, blew himself up in front of an Israeli post in Hasbayya in Southern Lebanon. His words of farewell to the Lebanese people were filmed and broadcast on national television, as is usual with suicide attacks.

1999.

Rabih Mroué, man of the theatre, and Elias Khoury, theatre director and writer, receive a video cassette on which three versions had been recorded of Jamal Sati’s last words. With each passing frame, his tone and bearing change. Khoury and Mroué watch it with growing amazement and a number of questions arise concerning “the variation in filming”. They decide to use it to make something and Three Posters was created.

2000.

The production was premiered at the Ayloul festival in Beirut. The question this production raises concerns the “martyr” and, more widely, the manipulation of information. For its makers, Three Posters is also an opportunity to cover the contemporary history of the Lebanon. Elias Khoury: “In contemporary history books about my country, no one talks about this war that lasted 15 years. It leaves the way open for the next civil war.” Three Posters mixes up testimonies: a (fictional) one by an actor, one by a real “resistance fighter” (Jamal Sati) and one by a communist politician who says how the resistance against Israeli occupation, which to start with was secular and multi-denominational, turned into Islamic resistance; how and why things slipped out of his hands.

Mei 2001.

During the KunstenFESTIVALdesArts, Walid Ra’ad, a Lebanese-American artist representing the Atlas Group, presents a reading between fiction and reality. He touches on a subject which is the common theme of many of our Festivals: the boundary between reality and representation and the way in which the media manipulates us on a daily basis, as much in countries like ours as 10,000 km away. We would have liked to present Three Posters at the same time as these readings, but scheduling difficulties meant the project was brought forward to this year.

Mei 2002.

The presence of Three Posters at the Festival is far from being straightforward after the events of 11 September 2001. Although it is a very sensitive subject, we decided to present it to you to emphasise the fundamental questions it raises and that concern all societies, ours as much as theirs. It is a world where censorship and violence, in all its forms, determines our lives all too often.

It was a coincidence when a friend fell upon Jamal Sati’s videotape. In 1962, Jamal Sati was born in a small village in Lebanon. He got enrolled in the Lebanese Communist Party in 1982, and became a member of the National Resistance Front in 1983. He participated in several military operations against the Israeli Army occupation.

In August 1985, Jamal Sati was killed after a suicidal operation against the headquarters of the Israeli military governor in Hasbayya in south Lebanon. The ‘martyr’ wore the clothes of a local ‘sheikh’ and led a donkey loaded with 400KG of T.N.T. After passing three barricades controlled by South Lebanon Army, he reached his target, exploded the T.N.T. and himself along with it.

Videotaping the resistance fighters declaring their testimonies before executing their suicidal operations became a common event. The videotapes were broadcasted on T.V. during the evening news.

Jamal Sati’s ‘final cut’ videotape first seen on Tele-Liban – the Lebanese public television channel – and it was a pure coincidence when a friend of our, after 14 years, fell upon his ‘uncut rushes’ videotape. It was in May 1999. She found it neglected, resting on a shelf in the offices belonging to the Lebanese Communist Party. The years of neglect had clearly left their marks, but also the filmmaker was not a professional, and the filming was done with a V.H.S. camera.

However, what astonished us was the repetition in the footage. We viewed the tape a number of times, and at every instance the extent of repetition left us with mixed feelings.

Question: What are the limits between truth and its representation? Jamal Sati was not an actor. Standing in front of a camera was a part of his political act of struggle; the operation was a suicide mission that sealed his fate. Why did he attempt to act? Is there something in the relationship between representation and death?.

Jamal Sati’s tape was shown on Tele–Liban once only. Could it be that representation resembles death in that it is only told once? We were confounded with this tape.

Lebanon was at the time, celebrating the liberation of its southernmost region from Israeli occupation. From the ranks of the National Resistance Front lead by the Lebanese Left, Jamal Sati was one of the first to undertake such a resistance mission. The Front, a prime instigator in the national call for the resistance, had been formed after the Israeli siege of Beirut in 1982, and the horrifying massacres of unarmed civilians in the two Palestinian refugee camps, Sabra and Chatila.

For us, who have been engaged in various forms of resistance, the question we have not been able to answer is, how do we tell a story enacted by its main hero before his death? Obviously, the larger political question is how did the resistance front begin as a secular and end up under the command of Hizbullah.

In the beginning, our idea was to simply show the videotape alone. The footage spoke by itself; it did not require assistance from us. Then we thought about returning the videotape where it belonged, re-enacting “performing” the story, recording it on a videotape in front of the audience. We would present spectators in the audience the chance to play the role of the ‘martyr’ and say what he or she wishes. Then we thought about merging the footage and the actor. The body of the actor would thus become a screen onto which the image of the ‘martyr’ is projected before his death, or rather after his death.

Finally the show we are presenting is a result of a decision to work within a simple framework. It proposes three possibilities for perceiving death: one actor, one resistance fighter: Jamal Sati, and one politician. The actor and the politician are the two invisible faces in the footage. We tried to group the three faces at successive instances. The actor fools us in the beginning but he reveals his own truth. The politician narrates the other voice of the story: how a moral defeat produces a political defeat. The actor acts only insofar as to unveil the stakes of his performance and its limitation. As for death, can only be understood in as far as it is experienced, and just then the need for expression dissipates.

Elias Khoury and Rabih Mroué

Rabih Mroué was born in 1967 in Beirut. He studied theatre at the University of Lebanon in Beirut and started in 1990 to produce his own plays and video performances. Since 1995 he has worked for television (Future TV) where he makes animated films and documentaries.

Elias Khoury is born in 1948 in Beirut, he studied history and sociology and taught Arab literature in Lebanon and the US (University of Columbia). He founded several literature magazines and is now editor of the weekly literary supplement of the daily paper An-Nahar. He has written eleven novels, two plays and one performance which have been performed in Beirut, Cairo, Paris, Vienna and Basel. He was artistic director of the Theatre of Beirut for six years and is now co-director of the Ayloul Theatre Festival in Beirut.

Concept & text : Elias Khoury, Rabih Mroué

Technical production : Georges Kerbaj, Lina Saneh

Production : Ayloul Festival (Beirut)

Supported by : l’Agence Intergouvernementale de la francophonie

Presentation : Halles de Schaerbeek, KunstenFESTIVALdesArts